"Pink Wave": A Note of Caution

News of the “Pink Wave” of women candidates was ubiquitous ahead of and after the first anniversary of the Women’s March. Cover stories and in-depth investigations into women running for office in 2018 rightfully celebrated the increase in the numbers of women running this year. At CAWP, we are the ones keeping those numbers, tracking potential candidates for Congress and statewide elected executive offices nationwide. We’re celebrating as well, thrilled to see women candidate numbers that are almost guaranteed to break records at every level. But we also know that there is more to this story, and ignoring important context in which to digest these candidate numbers risks inaccurate, and perhaps unfair, conclusions come Election Day.

So before we go surfing this wave, here are a few currents to consider.

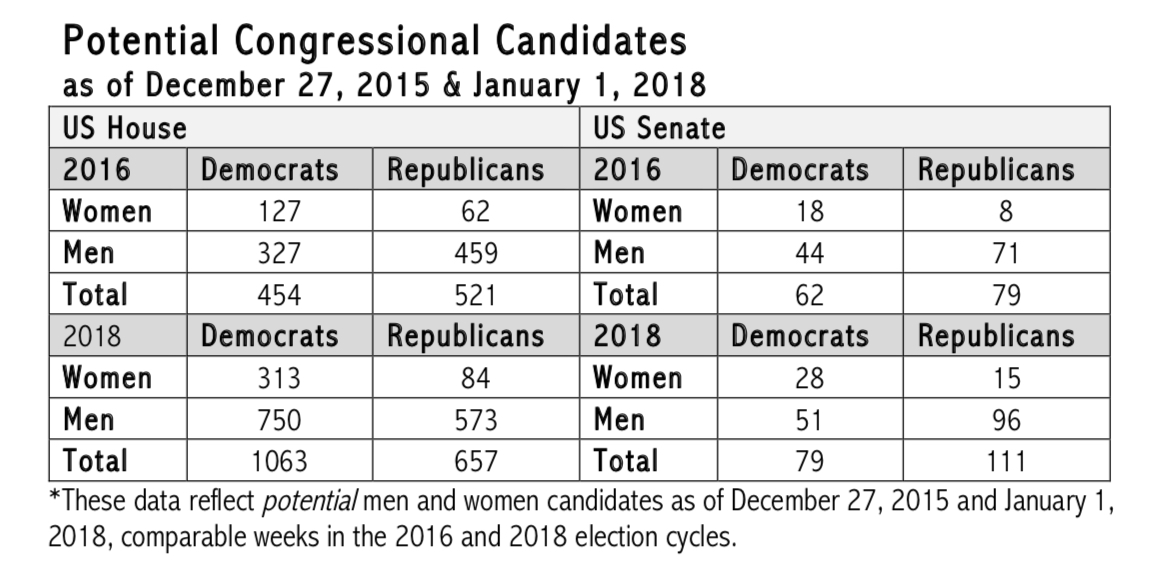

1. The surge in potential candidacies is not contained to women; more men are running too. And, like among women, the numbers of Democratic men likely to run for Congress has more than doubled from election 2016. We compared our list of potential candidates for the U.S. House and Senate at the start of the new year in both the 2016 and 2018 cycles. The number of Democratic male House candidates went up by 126%, while the number of Democratic female House candidates went up by 146% between these dates. Among potential Republican House candidates, the numbers for men went up 25% and women’s numbers increased by 35% at this point between the 2016 and 2018 cycles.

These data reflect potential women candidates at the start of each election year, not the number of women candidates who ended up on the primary ballots (as filed candidates) in these cycles.

Among likely Senate candidates, the gains are larger for women - Democrats and Republicans – than men from the 2016 to 2018 cycles, but women are not alone in increasing their numbers this year.

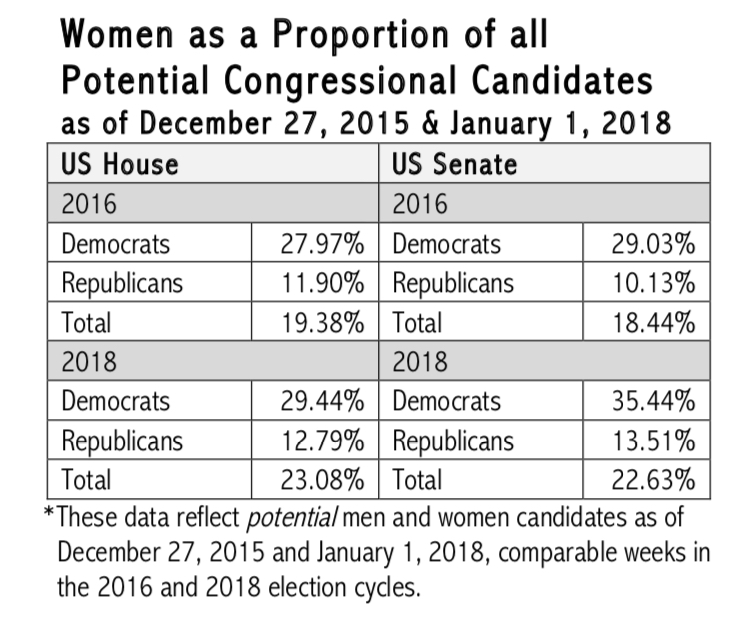

2. More women are running in 2018, but they are still less than a quarter of likely congressional candidates. Based on CAWP’s database of potential congressional candidates, women are just 23% of all individuals that have indicated they may file to run in 2018. This is up from about 19% of all potential congressional candidates at this point in election 2016, but – needless to say – is far from representative of women’s share of the U.S. population (52%).

The gain in women’s presence among the pool of likely candidates is notable, but may also be surprisingly low to many reading about a new “year of the woman.” When the rise among male candidates discussed above is taken into account, however, this makes much more sense. It’s only when women’s rise in candidacies significantly outpaces men’s that women will move closer to gender parity among potential congressional contenders.

3. The “Pink Wave” hues blue. The increases in women’s – and men’s – potential U.S. House candidacies are greatest among Democrats. Moreover, the representation of women among potential Democratic candidates for both the U.S. House and Senate is significantly higher than among potential Republican candidates, consistent with the disparities in representation among Democratic and Republican women in Congress today.

As of January 1, 2018, women were just under 30% of potential Democratic candidates for the U.S. House and 35.4% of potential Democratic Senate contenders. In contrast, women were just 12.7% of potential Republican House candidates and 13.5% of potential Republican candidates for the U.S. Senate.

Is this disparity consistent with previous cycles? Yes. The dearth of Republican women candidates is not unique to 2018. In fact, looking at the change in Democratic and Republican women’s proportions of their parties potential candidates from 2016 to 2018 shows the partisan story hasn’t changed much, especially among House contenders. The proportion of women among potential House Democratic candidates increased by about 1.5 percentage points from 2016 to 2018, while the proportion of women among potential House Republicans rose by three-quarters of a point.

Among potential Senate candidates, the proportion of women among Democrats jumped by 6 points from 2016 to 2018, while the proportion of women among Republicans rose by just over 3 points.

4. Many women running are swimming against the tide. As of this week, 59% of all potential women candidates for the U.S. House and 61% of all potential women candidates for the U.S. Senate are seeking to unseat incumbents, whether in primaries or in the general election. At this point in the 2016 cycle, 41% of all potential women House candidates and 52% of potential women Senate contenders were running as challengers. By historical comparison, 51% of file women candidates for the U.S. House were challengers in 1992, the “year of the woman” when women nearly doubled their congressional representation.

Celebrating the rise in women’s candidacies in 2018 is more than merited, but recognizing these electoral dynamics is important for a few reasons. First, being clear about the challenges women candidates will face in 2018 ensures that expectations of a drastic rise in women’s representation after Election Day are tempered and a more modest gain in women’s officeholding is not misinterpreted as a failure. Second, including men in our analyses provides a stark reminder of women’s overall underrepresentation among candidates and officeholders and, thus, the progress still left to make for women to reach parity with men in political power. Finally, these data should serve as motivation to push for greater women’s political empowerment on both sides of the aisle, both in this and future election cycles.

**HISTORICAL NOTE**

This is not the first time CAWP has issued caution ahead of a proposed "Year of the Woman." Check out this fall 1992 newsletter column from CAWP founder Ruth Mandel, which struck a similar tone. That year, women did nearly double their numbers in Congress, but remained just 10% of all members of Congress.