Which Women Give? Race/ethnicity and immigration factors in 2024 political giving

CAWP’s research has found that men’s total political giving exceeds women’s and that women from historically underrepresented racial/ethnic groups are particularly unequal. Donating to candidates is an important form of political participation: resources help candidates reach the ballot and mount successful campaigns.

I shed additional light on these dynamics with an analysis of newly available data from the 2024 Collaborative Multiracial Post-Election Survey (CMPS). The CMPS is the state-of-the-art dataset for studying the political attitudes and behavior of diverse Americans. Key findings from my working paper, which is focused on Asian, Black, and Latino/a/x Americans, include:

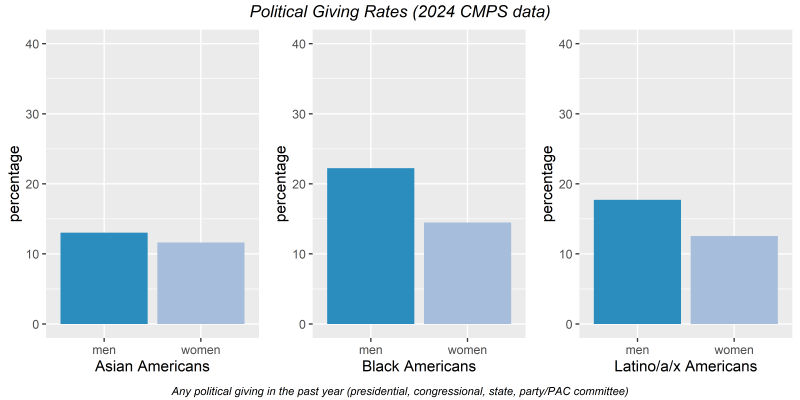

First, there was a gender giving gap (measured by the percentage of women and men who made a political donation in the past year). For both Black and Latino/a/x Americans, women were less likely than men to have made a campaign contribution. This means that Black women and Latinas were less likely than men in their communities to have helped their preferred candidates run for and win office through their financial support. Meanwhile, the gender difference for Asian Americans was not statistically significant.

Second, it’s often assumed that racial/ethnic inequality—which is often correlated with income and wealth inequality—prevents donations from diverse communities. And candidates may not seek campaign contributions from those communities as a result. I find that personal finances are often positively related to women’s political giving, though this relationship depends on the racial/ethnic group. But economic inequality isn’t the complete story.

My analysis sheds light on additional factors that explain political giving. If we look beyond variables such as income, we see that other factors are at work in understanding which women make campaign contributions. For example, women who attend religious services more frequently are more likely than other women to make campaign contributions; this is the case for all three racial/ethnic groups in my analysis. This may reflect the mobilization that often accompanies civic involvement – including religious involvement – as well as the degree to which immigrants are incorporated into their local communities.

Women with stronger partisan attachments were more likely than other women to contribute to candidates. And for Asian American women only, holding stronger ideological views was positively related to political giving.

Third, I find that the factors associated with political giving often vary by gender. For example, being born in the United States affects political giving for Asian American men but not Asian American women. Income is usually more strongly related to political giving for Black men than Black women. And primarily speaking English at home predicted Latino men’s – but not Latinas’ – political giving. Together, this evidence suggests that understanding the path to political giving should account for gender dynamics within communities.

Fourth, using the 2024 CMPS survey data, I conducted an analysis of giving to presidential candidates, restricting the analysis to those respondents who voted for or expressed support for Vice President Kamala Harris. Harris, who shattered fundraising records in her short campaign for president, presents a unique opportunity for research.

I find that, controlling for other factors, Black and Asian American women who supported Harris were not more likely than men from their racial/ethnic group to contribute to a presidential candidate in the past year. However, gender played a statistically significant role for the Latino/a/x American sample: Latinas who supported Harris were more likely than Latino men to report political giving in the presidential election. This finding, alongside the other analyses in the paper, confirms that understanding who does (and doesn’t) contribute is not solely a matter of economics.

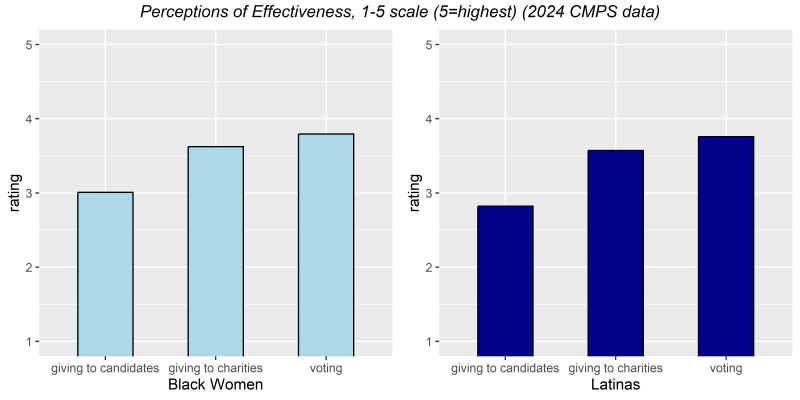

Fifth, the public doesn’t view political giving as positively as they view other political and civic activities. The 2024 CMPS includes (for Black and Latino/a/x Americans only) survey questions about the effectiveness of different activities in helping their communities. Women rated giving to candidates as less effective than voting or charitable giving on the 5-point scale, with 5 the highest rating. Part of the challenge, then, is for candidates, parties, and organizations to persuade potential donors that campaign contributions can impact issues they care about.

There are several implications here as we look to the 2026 election. Personal financial factors often shape political giving; after all (and by definition), money is required for campaign contributions. Growing inequality in the United States bodes poorly for equality of political voice.

At the same time, we do observe political giving by groups who – collectively – wield relatively modest economic power. Money matters, but it is not the sole answer to the question of who does and doesn’t give; giving is also shaped by immigration, religious commitments, and political factors. And we learn that gender, race/ethnicity, and immigration create different pathways to participation. Finally, given skepticism about the effectiveness of political giving, those seeking to mobilize new campaign contributors will need to win over hearts and minds, and not just pocketbooks.