Debate-Watching with a Gender Lens

This year’s primary debates provide us — for the first time this cycle — with an opportunity to observe and evaluate gender and intersectional dynamics among presidential contenders in a setting where they are directly engaging with each other. Here are some tips of how to watch this week’s debates with a gender lens.

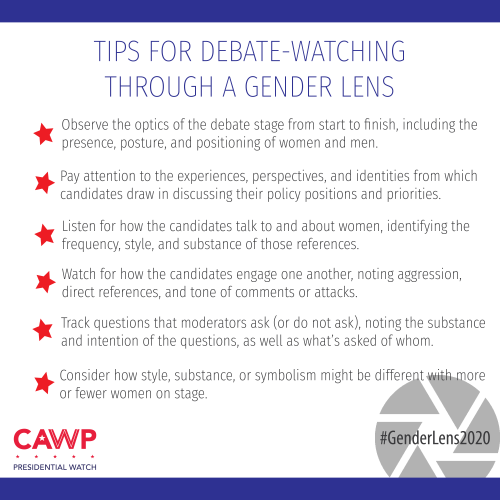

1.Observe the optics of the debate stage from start to finish, including the presence, posture, and positioning of women and men.

The presidential primary debate stages in 2019 and 2020 will look different than ever before. For the first time in U.S. history, more than one woman will stand with a group of men campaigning for the nation’s highest office. Instead of a single woman standing out in a sea of men, this year’s debates will offer alternative optics wherein women are no longer the exception to the norm. In addition to considering the symbolic importance of women’s proportional presence, the physical proximity between men and women candidates has the potential to influence voters. Whether it be in their evaluation of candidates’ body language or even differences in height (yes, that’s a thing), debate viewers are able to react to candidates in relation to each other rather than independently, as is most common in the campaign season. These settings are ripe for gendered considerations, especially due to norms about male-female interactions and because of the ways in which physical traits have historically acted as cues for leadership.

2. Pay attention to the experiences, perspectives, and identities from which candidates draw in discussing their policy positions and priorities.

What has the dominance of white men on debate stages meant for the content of presidential campaign conversations throughout U.S. history? Beyond the singular optics, this has narrowed the range of experiences and perspectives represented in presidential debates. With greater diversity of backgrounds and lived experiences present in this year’s Democratic primary debates, it’s worth noting where and how candidates draw upon their multiple identities — including race and gender — to make the case for candidacy and/or to stand apart from the crowd. When Elizabeth Warren talks about her Aunt Bee stepping in to help her juggle work, school, and caring for her young kids, she offers a first-person perspective that’s especially relevant to justifying the need for more robust child care support to working parents (among whom women continue to bear the brunt of caregiving responsibilities). Just this week, Kamala Harris drew upon her direct insights into racism to explain her passion for empowering all women to control their own bodies. At Planned Parenthood’s candidate forum, she explained that as a daughter of an Indian-American woman, she had watched people assume “a five foot brown woman had no power and should be given no power” and vowed to stop it.

Beyond informing policy dialogue, having diverse voices on the debate stage can bring starker contrast to the conversation. For example, when Jake Tapper raised Trump’s treatment of women in a 2016 Republican primary debate, he asked candidate Carly Fiorina directly about comments Trump made about her face. Fiorina’s response was simple but resonant with women viewers: “I think women all over this country heard very clearly what Mr. Trump said.” Likewise, when Brian Williams raised the issue of Barack Obama’s religion in a 2007 debate, Obama reminded viewers of the additional work he had to do — as a Black man — to overcome bias. “There is no doubt that my background is not typical of a presidential candidate,” he responded, adding, “I think everybody understands that, but that’s part of what is so powerful about America is that it gives all of us the opportunity — a woman, a Latino, myself — the opportunity to run.”

In this year’s debates, paying attention to the perspectives that are new to the debate stage — as well as those that are missing — will provide helpful insights into the value of diverse voices in engaging viewers of all types and informing policy conversations.

3. Listen for how the candidates talk to and about women, identifying the frequency, style, and substance of those references.

Importantly, it is not only women candidates who talk to or about women — or at least it shouldn’t be. It is critical for men and women candidates alike to appeal to women voters, especially because women voters make up the majority of Democratic voters. But do they recognize the diversity among women instead of assuming that all women share the same experiences, policy priorities or positions? Are words backed by actions and plans? Calling your opponent a “nasty woman” just minutes after saying, “Nobody has more respect for women than I do” — as Trump did in an October 2016 debate against Hillary Clinton — reveals the disconnect between words and actions.

The genuineness of candidates’ claims for women’s equality and empowerment can also be evaluated in their knowledge of how policies and politics have affected different groups of women, as well as in their efforts to understand policy from diverse women’s perspectives. Are candidates engaged in true allyship with women — which also means appreciating the constraints on their understanding — or do their efforts to prove they are champions for all women keep the focus on them?

With more women on Democratic debate stages this cycle, there will be more opportunities than in previous presidential contests to observe how men (and women) speak to women, not just about them. And these interactions are not only between candidates, but also between candidates and moderators, who will also include women in every Democratic debate.

4. Watch for how the candidates engage one another, noting aggression, direct references, and tone of comments or attacks.

My own research suggests that male candidates are often particularly concerned about being perceived as bullying a woman opponent in interpersonal settings like debates. While Trump appeared perfectly comfortable stalking Clinton on a 2016 townhall stage, many men have been warned against having their “Lazio moment,” referring to the moment when Senate candidate Rick Lazio invaded Hillary Clinton’s personal space in a 2000 debate to demand she sign a pledge to forgo soft money donations to her campaign. The optics would have been bad enough had Clinton been a man, but the backlash was heightened among those who saw Lazio’s aggression as an attempt to intimidate Clinton and/or something he would not have done against a male opponent. Smaller considerations that both men and women make are how to refer to their opponents (first name or titles) to best reflect their respect, or if/how they engage physically before or after the debates (handshakes, hugs, or avoidance have all been seen in the past).

The research on gender dynamics and negative campaigning reveals mixed findings on whether or not women will be penalized for attacking opponents, though most of the literature suggests that attacks on substance yield little backlash. In fact, when women stand up to opponents they can prove to voters their passion and preparedness for political leadership. While practitioners will still note the need for women to be aware of tone — perhaps more than men — in debates and on the campaign trail, it’s unlikely that the women running for president this year will hold back in taking on individuals or issues with whom they disagree.

5. Track questions that moderators ask (or do not ask), noting the substance and intention of the questions, as well as what’s asked of whom.

The debate moderators play a big role in shaping the conversation on stage. That’s why it’s important to consider what they are asking — and of whom they are asking it. Consider, for example, whether the debate moderators are asking questions about gender equality to women and men candidates, and questions about racial equity to candidates of color and white candidates. Putting the onus on candidates who represent marginalized groups to explain — and resolve — that marginalization is a problematic, yet common, approach to conversations of racial and gender equity. However, debate moderators have the chance to push men — particularly white men — candidates to interrogate their gender and race privilege in the context of politics and policy. Already some journalists have done this by asking white men if they would promise gender equity on their presidential ticket. While women and candidates of color have long been asked to justify their inclusion in politics because they have stood apart from the norm, this and similar questions have forced men to consider the normalization of men’s presidential leadership as inherently unequal.

Hickenlooper: “How come we’re not asking, more often, the women, ‘Would you be willing to put a man on the ticket?’” pic.twitter.com/Ue8mkzJG3A

— Shane Goldmacher (@ShaneGoldmacher) March 21, 2019

Women candidates have previously contended with questions about the men in their lives — husbands, fathers, previous partners — whether due to those men’s missteps or attempts to paint women’s success as reliant on these relationships. This requires women to reaffirm their independence and refocus the conversation on their own records. Hillary Clinton did this masterfully in a 2008 Democratic Debate when moderator Tim Russert tried to pin her to a position held by her husband, former President Bill Clinton. After Russert noted the difference in position between her and Bill, Hillary Clinton quipped of her husband, “He’s not standing here right now.”

6. Consider how style, substance, or symbolism might be different with more or fewer women on stage.

Democrats have held just over 100 primary debates since 1956 and women have appeared in 41 of them. That number does not seem so bad until you realize that just three women — Shirley Chisholm, Carol Moseley-Braun, and Hillary Clinton — have ever participated in Democratic primary debates, compared to 29 men, and never has more than one woman debated at the same time in the past five decades. Here’s one more statistic for you: women account for about 8% of nearly 500 individual Democratic debate appearances since 1956 (and Hillary Clinton alone accounts for 6%).

Until this year, we had little to work with to consider how greater diversity among candidates’ gender — or race, and especially the intersection between gender and race — would change the substance of debates and/or how they were received by viewers. There is an opportunity to evaluate those dynamics this year, but there is also still value in thinking about what might be altered if the make-up of the debate stage were demographically different — including candidates and moderators. While there will be more women on stage this year, what voices — among men and women alike — are still missing? And how might that shape the conversation?

Follow @CAWP_RU on Twitter for real-time analysis of the Democratic primary debates and share your own insights using the hashtag #GenderLens2020.