Money and Gubernatorial Races: How are Women Faring as Candidates and Donors?

Despite a historic year for women in politics that featured the election of the first woman vice president and a new record for women in Congress, 2020 did not see any new women elected governor. Just nine women serve as governors across the fifty states. And in 2018, which also saw records for women winning seats in Congress and state legislatures, there was no new record set for women governors despite the large number of gubernatorial elections that year.

The Money Hurdle in the Race for Governor, the first report in the new CAWP Women, Money, and Politics series, sheds light on the challenges and opportunities for women governors and women donors. The report is the most comprehensive study of money and gender in gubernatorial elections conducted to date. CAWP is grateful to Pivotal Ventures for making the report possible. Pivotal Ventures is an investment and incubation company founded by Melinda Gates.

Our report reflects a collaboration between CAWP and the National Institute on Money in Politics (NIMP). NIMP’s database is a unique resource for researchers and practitioners: NIMP compiles and cleans contributions data from state disclosure agencies, and identifies donor gender, for all 50 states.

While other researchers have investigated the relationship between campaign finance and women candidates, this research has almost exclusively focused on congressional elections rather than gubernatorial elections.[i] The neglect of gubernatorial office is unfortunate, particularly because the cost of running for governor is increasing. The current number of women governors—nine—is the highest number of women ever to serve simultaneously and a record first set in 2004. According to CAWP’s data on women governors, only 44 women have ever served as governors; twenty states have yet to have a single woman governor. Just three women of color have ever won the office of governor; a Black woman or Native American woman has yet to win the office.

Our report provides a comprehensive analysis of contributions from individuals extending from 2000 to 2018 using CAWP and NIMP data. Our analysis includes primary elections, which is a neglected topic in campaign finance research.[ii] New women candidates for governor must first secure their party’s nomination, and since parties are often neutral in primaries, these candidates are competing within their parties for contributions. We also include an analysis of general election contributions with a focus on mixed-gender (woman v. man) contests. Finally, we rely on NIMP’s estimates of the gender of contributors to determine the extent to which women are represented in the donor pool for gubernatorial candidates.

Here are some key takeaways from our report:

Women’s political voice is not equal to men’s with respect to campaign contributions.

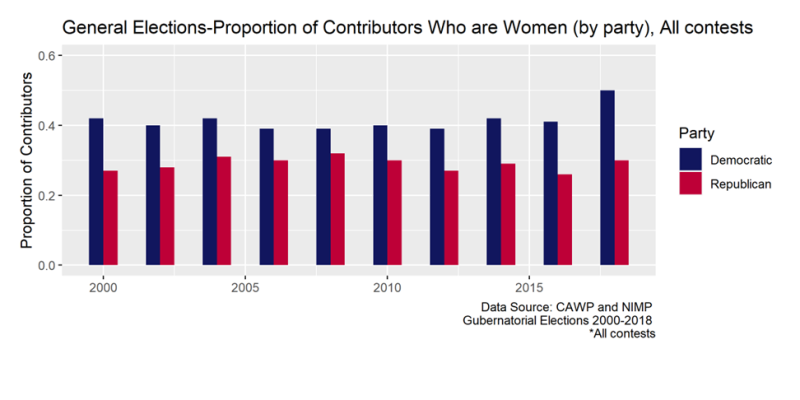

Looking across gubernatorial contests (primary elections without incumbents, and all general election contests), women are underrepresented as contributors. For example, our analysis of general election contests reveals only one case (women donors to Democratic candidates in 2018) in which women were about half of donors. In all other cases, men constitute the majority of contributors.

Women are more likely to give to women gubernatorial candidates than men, and women are more likely to give to Democrats than Republicans.

In both primary contests without incumbent candidates and mixed-gender general election contests, women are better represented as contributors to Democratic women candidates than Democratic men candidates for governor. The same holds for women donors to Republican primary candidates, though our analysis finds more similar statistics for women and men who give to Republican general election candidates.

The total amount of gubernatorial campaign contributions given by women is less than what men give.

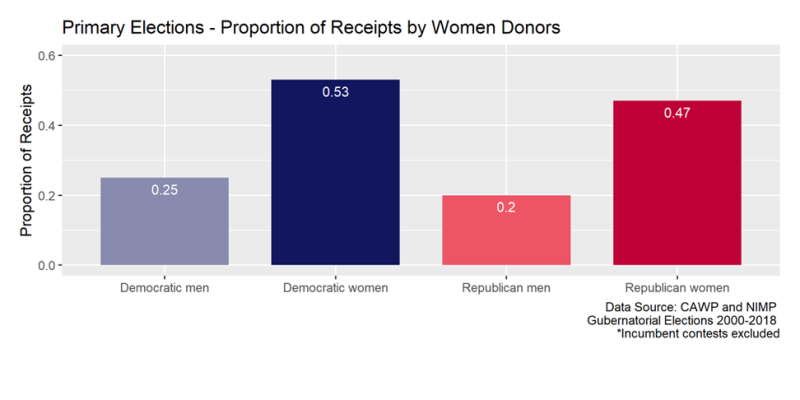

In both primary contests without incumbent candidates and mixed-gender general election contests, men provide most of the money raised for gubernatorial candidates through individual contributions from 2000 to 2018. However, when we disaggregate by candidate party and gender, women’s contributions represent about half of the money raised in primary election receipts for women candidates in the same period.

Women are underrepresented as gubernatorial candidates. This is especially true for women of color and Republican women.

While women were just under one-quarter of Democratic primary candidates in contests without an incumbent, women were only about 10% of Republican primary candidates between 2000 and 2019. And just 2.6% of primary candidates in this period were women of color.

Money matters in gubernatorial elections.

The relationship between fundraising and winning is not guaranteed. But money is a valuable resource in elections. We find that the gubernatorial candidates who raised more money were more likely to win their races.

Women gubernatorial candidates are competitive fundraisers.

Most of our analyses of primary and general election contests find similarity in how much money women and men raise as gubernatorial candidates, particularly when other factors such as the type of race are taken into account.

We find important gender, race, and party differences in the structure of gubernatorial campaign receipts.

Although women and men raise similar amounts, women primary candidates for governor are more likely to have held prior office than men primary candidates suggesting that qualification standards are higher for women candidates.

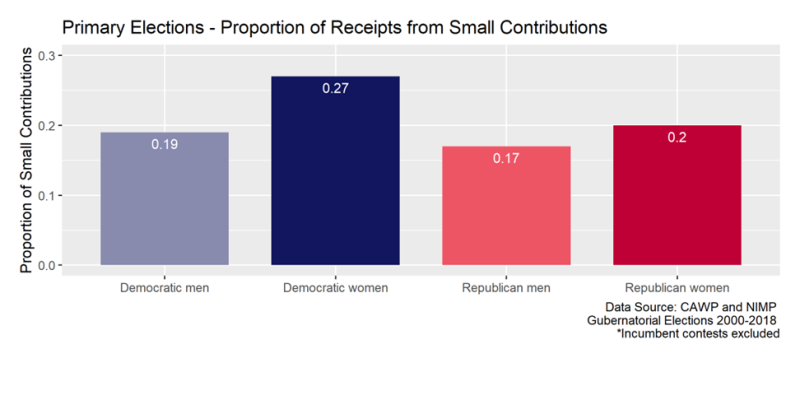

We also find gender differences in how women and men raise money. In most of our analyses, we find that women are more likely than men to raise money through small contributions. This may mean that women expend more effort than men to raise the same amount of funds.

More women can seek gubernatorial office, and more women can give to gubernatorial candidates.

Women are the majority of voters, and Democratic women are approaching parity with Democratic men within Congress. Yet few women hold gubernatorial office. Given that women can successfully raise large sums for their gubernatorial candidacies, we believe that many more women could run successfully for governor. More investment by donors, particularly at the critical primary stage, could increase the number of women running for and winning these offices.

Recent studies reveal an increase in women’s participation as donors in congressional races. Women can continue to amplify their political voice by playing a larger role in giving to gubernatorial candidates than they do now. And because states play a crucial role in American politics, women’s involvement as gubernatorial campaign donors and success as gubernatorial candidates could yield public policy that is more reflective of women’s voices.

[i] For an exception see Sanbonmatsu and Rogers 2020.

[ii] Our primary elections analysis focuses on contests without an incumbent candidate. See the report for the complete methodology.