Teaching Tool: Applying Gender and Intersectional Lenses to U.S. Elections

Teaching about politics and government in the current political context means grappling with both longstanding dynamics and new and evolving realities. It also requires providing students the necessary tools to understand today’s political events through multiple and layered lenses of analyses. Gender and race, and importantly the intersection of both, have forever shaped U.S. political institutions, from the legal exclusion of women and communities of color from political participation to the persistent biases in formal and informal political rules and practices that favor white men. These dynamics have created disparities in opportunity, experience, and power within political institutions. Those disparities persist, even amidst evidence of progress, and require recognition and understanding en route to resolution.

Educators play an important and influential role in fostering this type of recognition and understanding among students. Across course types and titles, educators have the opportunity to equip students with the ability to view political institutions, events, and dynamics through gender and intersectional lenses. In this blog, I share some ideas and resources for doing this work, using the 2020 presidential election and CAWP’s new digital timeline as primary tools for explanation, illustration, and application of these concepts.

Defining Concepts

Evaluating politics and government through gender and intersectional lenses means revealing the ways in which those institutions are shaped by gender and race, and the intersection of both. One way to root this discussion is to provide students with explanations of concepts like gendered institutions and intersectionality.

There are many helpful literatures on both of these concepts from which instructors can draw definitions and key tenets for analysis. One example is Joan Acker’s 1992 essay on gendered institutions, where she explains how “gender is present in the processes, practices, images and ideologies, and distributions of power in the various sectors of social life” (567). Acker’s processes and practices can also be considered with attention to race within U.S. institutions. There are many helpful resources that provide both historical context for and explanation of intersectionality theory, developed by Kimberlé Crenshaw. In addition to assigning Crenshaw’s seminal articles on the concept, Wendy Smooth’s 2013 chapter, “Intersectionality from Theoretical Framework to Policy Intervention,” provides an accessible guide to theory history, content, and application. Smooth defines intersectionality as “the assertion that social identity categories such as race, gender, class, sexuality, and ability are interconnected and operate simultaneously to produce experiences of both privilege and marginalization” (11).

These are just two of many valuable resources to guide instruction on gender and intersectional analyses. They provide a helpful foundation upon which other scholarship can build and expand lessons that will prepare students to apply these concepts to historical or modern-day events and institutions.

Applying Gender and Intersectional Lenses

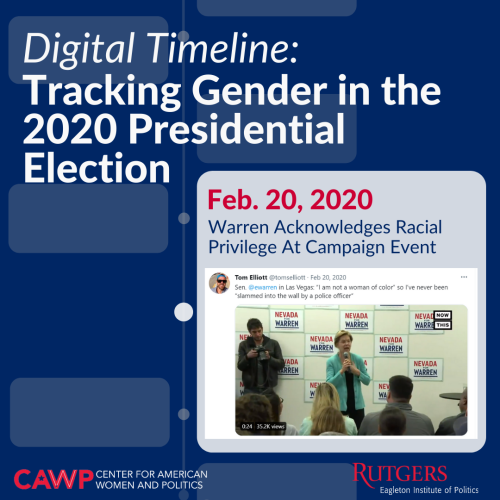

How can instructors bring these concepts to life for students? Applying concepts of gendered institutions and intersectionality to real-world institutions and events can make tangible the theoretical frameworks described above. CAWP’s new resource – Tracking Gender in the 2020 Presidential Election – not only provides a helpful illustration of how this application can work, but also gives both students and instructors more than 300 individual examples of how gender and race continue to shape: the ways in which candidates – women and men – navigate campaigns; the ways candidates are perceived, evaluated, and treated by voters, media, and opponents; and the ways in which voters make electoral decisions. The timeline pairs embedded videos, graphics, and social media content with short analyses, sortable tags on key concepts (e.g. electability, gender bias, masculinity, white privilege), and an introductory essay that summarizes key themes that were evident in the 2020 presidential election. Instructors might consider various approaches to using this new teaching tool in their courses.

Instructors could assign Tracking Gender in the 2020 Presidential Election, asking students to read its introductory essay and review the digital timeline before discussing it in class. Pairing this assignment with guiding questions would help the students focus on key concepts. Possible guiding questions include:

- In what ways did gender and race shape the 2020 presidential election?

- In your view, what 2020 presidential election events or dynamics indicate gender and/or intersectional progress in presidential politics? What events or dynamics indicate persistence of gender and/or intersectional barriers or biases in presidential politics?

- Are similar gender and intersectional themes evident outside of presidential politics? What examples might you point to as illustrations of these realities at different levels of office and/or outside of elections?

- What is missing from this analysis? What would you add to the discussion of gender and intersectional dynamics in the 2020 presidential election?

- What other “lenses” might be applied to the 2020 presidential election to enhance our understanding of it? Can you provide an example of how you might apply that lens to a specific election event?

Instructors could ask students to review the digital timeline and choose one or multiple posts for their own, more detailed, analyses through gender and/or intersectional lenses.

For example, the timeline highlights comments from Kirsten Gillibrand and Elizabeth Warren on their racial privilege as well as disparate treatment they faced by media regarding their likability and electability, pointing out Smooth’s emphasis on the coexistence of privilege (in this case racial) and marginalization (in this case gender). Another post details how Amy Klobuchar and Elizabeth Warren asked for forgiveness for their passion at a December 2019 debate, illustrating both their awareness and the reality of bias in evaluations of women’s expression of emotion. No men on stage asked for forgiveness for anything, especially not for anger or enthusiasm, because that same passion is perceived as a positive attribute of political men. This exchange reflects Acker’s discussion of the “construction of personas that are appropriately gendered,” with women candidates feeling pressure that men do not to explain and justify why their campaign personas sometimes conflict with perceptions of appropriateness for their gender.

Instructors could utilize the timeline’s tags to split a class into sections of students that would review specific tags and report back to the class with an overview of what 2020 presidential election events revealed about those themes or concepts.

For example, choosing the “electability” tag filters the timeline for posts that provide both evidence of and explanations for gender and intersectional biases in who was perceived as electable in the presidential contest. Students will find posts that use polling to demonstrate voters’ concerns about women’s electability as well as examples of how candidates sought to address electability concerns – like when Warren shifted messaging to emphasize that “women win” – or even capitalize on them – like when Biden urged Democratic voters not to take any risks in selecting their presidential nominee. The extra work required of women candidates – and, even more specifically, women of color – to make the case that they could win the nation’s highest office demonstrates the institutional norms and intersectional biases in presidential politics that create disparate conditions among candidates by gender and race.

Instructors could forgo assignment of the essay or timeline but use both/either to generate illustrations of gender and intersectional concepts for in-class teaching, using videos, images, or social media examples to supplement lectures.

In assessing possible progress in presidential expectations, instructors might have students review the comment made by candidate Beto O’Rourke about how his wife is “raising, sometimes with my help” their children. This comment, the backlash to it, and O’Rourke’s swift apology, demonstrate how men may be held to a new standard in acknowledging the gender disparities in caregiving responsibilities and, moreover, recognizing their implications for equity in both private and public life. In contrast, other videos available on the timeline – such as Donald Trump promising to get women’s “husbands back to work” or Biden’s “That’s a President” ad – exemplify the persistence of masculine presentation strategies by presidential candidates.

In addition to utilizing this new resource, be sure to check out CAWP’s website for many more resources and tools that can supplement instruction on gender, race, and U.S. politics.