A Woman Running Mate is Just a Start

Joe Biden made news in last night’s Democratic debate for stating definitively that he would choose a woman as his running mate if he wins his party’s presidential nomination. While leaving himself an out, Bernie Sanders said he would “in all likelihood” choose a woman as well. The prospect of a mixed-gender ticket is more notable than it should be in 2020. Four years ago and again in recent months, there was talk of the possibility of an all-woman presidential ticket. But with no viable woman candidates remaining in contention for the presidential nomination, the number two slot is now the only chance for a woman to be on a major-party ticket.

And while it seems to many that gender balance on a presidential ticket should not be exceptional, it is. All-male tickets have been the norm in presidential politics for over 200 years. Only three women have ever appeared on major-party presidential tickets, with two as vice presidential running mates to male nominees. In the past 100 years, just 3 of 100 names on major-party presidential tickets have been women.

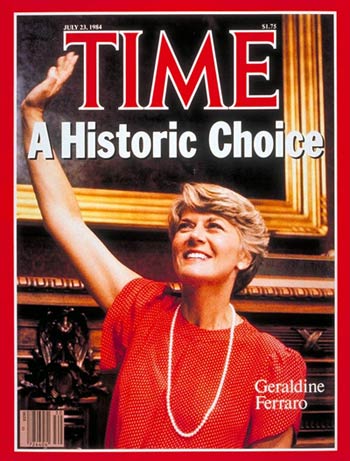

The first woman on a major-party presidential ballot was Geraldine Ferraro, who Democratic nominee Walter Mondale selected as his running mate in 1984. Ferraro’s selection was the result of feminist activism and lobbying, in which organizations like the National Organization for Woman (NOW) sought to leverage the power of women’s votes – especially the gender gap that had first emerged in the 1980 election – to pressure the Democratic Party to address women’s demands. Those demands were not limited to a woman on the ticket. As Susan Carroll details in a chapter about this period, “Over the course of discussions among feminist activists and organizational leaders, the idea emerged to push for the selection of a woman as a vice-presidential candidate in 1984 as ‘an attention-getting device’ to build on the momentum generated by the gender gap and ‘keep women’s issues on the front burner of American politics and that meant the front pages of the newspapers and on the evening TV news shows.’“

The first woman on a major-party presidential ballot was Geraldine Ferraro, who Democratic nominee Walter Mondale selected as his running mate in 1984. Ferraro’s selection was the result of feminist activism and lobbying, in which organizations like the National Organization for Woman (NOW) sought to leverage the power of women’s votes – especially the gender gap that had first emerged in the 1980 election – to pressure the Democratic Party to address women’s demands. Those demands were not limited to a woman on the ticket. As Susan Carroll details in a chapter about this period, “Over the course of discussions among feminist activists and organizational leaders, the idea emerged to push for the selection of a woman as a vice-presidential candidate in 1984 as ‘an attention-getting device’ to build on the momentum generated by the gender gap and ‘keep women’s issues on the front burner of American politics and that meant the front pages of the newspapers and on the evening TV news shows.’“

In recent weeks, a coalition of 11 women’s organizations made a similar case to 2020 presidential candidates. In their petition, they called upon all presidential candidates to not only select a woman for vice president, but to commit to gender parity, as well as racial and religious representation, in presidential appointments. But again, their case does not solely rest on women’s descriptive presence; they argue that women’s descriptive representation will yield substantively positive results for women. The organizations write, “We know that the only way to guarantee that women’s issues stay on the agenda is if women are the ones setting it.”

Decades of research on the impact of women officeholders backs the claim that women’s inclusion alters agendas and priorities in ways that benefit women in the electorate. Still, today’s presidential candidates should not put the onus on a woman running mate to carry the water in outreach to women and/or in applying gender and intersectional lenses to policy and politics. The white men who will top presidential tickets in 2020 need to do more than tapping women to make clear that they not only understand the distinct experiences, needs, and demands of women, but will value and integrate them into their policy plans and priorities. They will also need to demonstrate their capacity to recognize and address the full diversity among women, and thus the diversity of women’s needs and demands.

It is hard to know what the effects of a woman vice presidential nominee on the Democratic presidential ticket in 2020 will be. What we do know is that it is unlikely to influence many votes on Election Day. Both men and women voters are guided much more by party affiliation than any other factor in casting their ballots. A CNN/ORC poll in 2016 revealed, for example, that vice presidential picks were especially unimportant to voters’ decision-making; 86% of registered voters said it would make no difference to their vote if Hillary Clinton chose a female running mate and 89% of registered voters said Trump’s selection of a woman running mate would make no difference in their decision to back him or not. Similarly, historical precedent proves prescient here; neither the Democratic selection of Geraldine Ferraro in 1984 nor the addition of Sarah Palin to the 2008 GOP ticket brought a discernable influx of unexpected or unlikely voters to their camps. Beyond gender, these findings reflect the reality that voters are most concerned about the top of the ticket and less concerned about who is VP - woman or man.

This does not mean that putting a woman on the ticket will not matter at all, particularly in a political environment where issues of gender equality are especially salient and in a year when either Democratic candidate would become the oldest president elected if successful in November. The presence of a woman on a presidential ticket could mobilize some voters, or at least be among a set of factors that influence their behavior. While the Mondale-Ferraro ticket was defeated at the ballot box in 1984, feminist leaders and activists claimed Ferraro’s selection was a success. For example, as Carroll details, Gloria Steinem claimed that Ferraro’s candidacy was “a substantial net plus in activism,” with Ferraro raising $4 million for the ticket and attracting 10,000 volunteers. Other leaders pointed to the registration of 1.8 million new women voters in advance of the 1984 election as evidence that having a woman on the presidential ticket mattered. Scholars David Campbell and Christina Wolbrecht suggest that the positive impact of Ferraro’s candidacy may have extended to young women, finding that adolescent girls became significantly more likely to express an interest in political activities (e.g. writing to public officials, giving money to a political campaign, or working in a political campaign) in the year after Ferraro was on the ticket.

The last time Democrats nominated a woman for vice president, adolescent girls became significantly more likely to express an interest in political activities, such as working on a campaigns. cc: @CAWP_RU https://t.co/0sxlPeK5jW pic.twitter.com/Yp2ckvl9nm

— Christina Wolbrecht (@C_Wolbrecht) March 16, 2020

However, Sarah Palin’s addition to the 2008 Republican presidential ticket did not seem to have a similarly positive effect on young women’s political engagement, consistent with research showing that the mobilizing effect of women candidates is conditional on political context and partisan cues. Moreover, there is reason to believe that the positive effects of adding a woman vice presidential nominee in 2020 – when many feel that the time for a woman president is overdue – might vary from nearly four decades ago. Concerns that this year’s addition of a woman is simply a consolation prize for not winning the ticket’s top spot, beliefs that a gender-balanced ticket is overdue, and demands that the candidates do more than select a woman to demonstrate competency on gender equity are likely to depress the enthusiasm that emerges as a direct result of the selection of a woman VP.

Finally, which woman is selected as a vice presidential nominee in 2020 will likely matter more than the fact that a woman is on the ticket. Voters – women and men alike – will be concerned about the experience, perspective, and priorities of potential woman running mates, in addition to their ability (if any) to mobilize and attract particular groups of voters in a general election contest against Donald Trump. Candidates should be careful not to assume uniformity in women’s appeal as candidates or in women’s perspectives and priorities as voters. Even in 1984, a poll commissioned by the National Women’s Political Caucus (NWPC) found that a woman’s positions on issues and her experience were more important to voters than the fact that she was a woman. Carroll cites Florence R. Skelly, president of the firm that conducted the poll, who concluded, “This study shows they can’t just name to that ticket and have it work... Even with sisterhood and the gender gap, you can’t automatically attract women’s votes with a woman candidate.” Biden and Sanders would be smart to heed the same caution in 2020. Selecting a woman vice presidential nominee is a minimum, not solitary, step toward making good on a commitment to gender equity in the next presidential administration.