Woman vs. Woman Races: Gender Exclusivity for Gender Inclusivity?

Even before odd-year elections in states like NJ and VA are over, we’re looking ahead to the 2014 midterm elections for opportunities to increase women’s representation. In a year when 36 states will hold gubernatorial elections and another 32 states will elect (or re-elect) U.S. Senators, will women move forward on the path toward political parity? It’s too early to predict electoral outcomes, but CAWP is keeping track of women who have put their names forward as potential candidates for statewide or federal office. By looking at these early lists, we can get an initial sense of how many and where women are running, and how the pattern compares to candidate statistics at this point in previous cycles. Over the next year, we will report on trends we spot, interesting facts we find, or news you can use about women in the 2014 election in our news alerts and on this blog. This week, we’re looking at woman vs. woman races. How many have we had? Do we expect any women-exclusive races in 2014? And what’s the political significance of such races? Based on our latest counts, women are potential challengers to three of the four incumbent women senators up for re-election in 2014. Women are also running in both major party primaries for open Senate seats in Georgia (Democrat Michelle Nunn and former Republican Secretary of State Karen Handel) and West Virginia (Republican Congresswoman Shelley Moore Capito and Democratic Secretary of State Natalie Tennant). No women have yet emerged to challenge the four incumbent women governors up for re-election next year, but many women have put their names forward as potential gubernatorial contenders in Florida, Massachusetts, and Pennsylvania. Finally, as of today, women are running for both major party nominations in eight U.S. House districts, and another six districts have more than one woman running in either party’s primary. Historically, woman vs. woman races for federal and statewide offices have been very rare. Of all general election U.S. Senate races to date, only 12 have pitted a Democratic woman against a Republican woman, and three of those contests occurred in 2012 alone. Women have faced each other in only four gubernatorial races in U.S. history, with two of those races in 2010 (in Oklahoma and New Mexico). Finally, while there have been 134 woman vs. woman elections for U.S. House seats over time, these represent less than a third of House elections held in any single year. Some might argue that woman vs. woman races are not necessarily a sign of progress, that pitting women against women could actually be harmful to women’s representation, or that gender exclusivity for men or women is an unjust goal. Each of these arguments has merit and is worthy of greater debate. However, it is hard to say that increasing evidence of woman vs. woman races does not signal at least some progress. At the least, woman vs. woman races reflect an increased willingness among women to run for the highest levels of elected office – and a willingness among parties and voters to elect them.

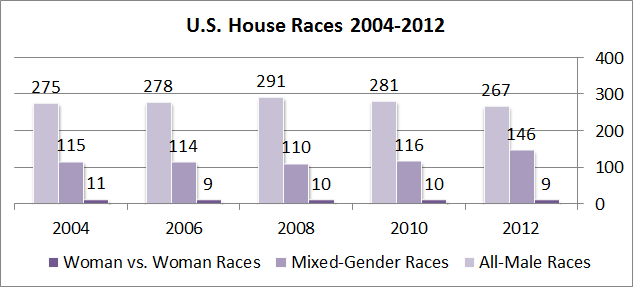

And for those who fear gender exclusivity of any stripe, let’s look at recent electoral history. Over 60% of general election U.S. House races in the past decade have been all-male contests, and 85% of uncontested candidates have been men.

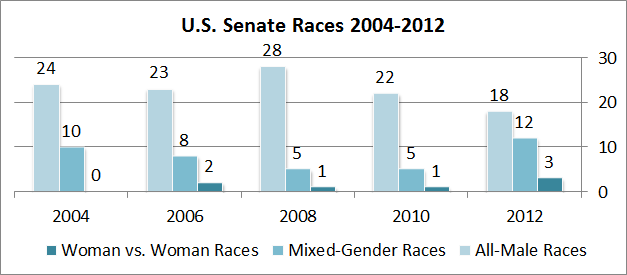

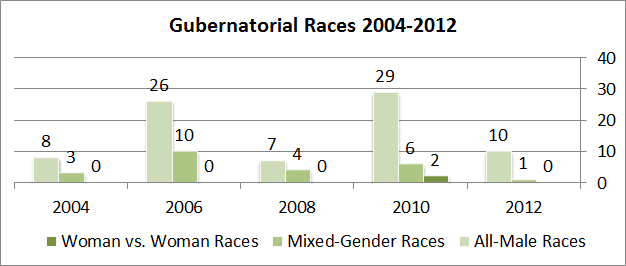

About two-thirds of general election races for the U.S. Senate have been between two male candidates, and 80 of 106 gubernatorial races between 2004 and 2012 had no women. In contrast, about 2% of U.S. House races, 4% of U.S. Senate races, and less than 2% of gubernatorial contests in the past decade have been all-female. And of course, men-only races at each of these levels of office only increase the further back we look.

Gender exclusivity in electoral contests should not be a goal, but it has been a reality for male candidates for far too long. For women to increase their political representation, they need to be more present as candidates. And if woman vs. woman races are a surefire way to get more women into office, then maybe an increase in gender exclusivity for women candidates actually means greater gender inclusivity in today’s politics.