With the rise of the #MeToo and the Black Lives Matter movement, Americans found refuge within social movements to express their political grievances (Edrington and Lee 2018; Ince, Rojas, and Davis 2017; Jaffe 2018; Leopold et al. 2021; Mundt, Ross, and Burnett 2018; Nummi, Jennings, and Feagin 2019). Notably, both the #MeToo movement and the #BlackLivesMatter movement, two of the most significant and farthest-reaching social movements in recent American politics (Buchanan, Bui, and Patel 2020; Leopold et al. 2021), were founded by Black women. However, mainstream media coverage of both movements obscures their intersectional origins. Wealthy, white actresses became the symbolic face of the #MeToo movement following the social media blowup of the hashtag that led to the ouster of media mogul Harvey Weinstein. Tarana Burke, #MeToo’s founder, laments that this moment became the movement’s most symbolic case, as it shrouds the everyday sexual violence the movement was intended to address.1

Additionally, Burke noted that even the movement’s discussions in social media and public forums fail to center what she calls the “untold stories” of women of color, and specifically Black, trans, and Indigenous women. Burke notes that the pain of women belonging to these groups “is never prioritized.2 Burke herself is a dark-skinned Black woman with natural afro-centric style of hair, a stark contrast to the white celebrities that co-opted the movement.

In Brown and Lemi’s s 2019 study, they found that internal discrimination, also known as colorism, heavily influenced candidate preferences as respondents showed greater support toward light-skinned Black candidates with straightened or looser hairstyles, penalizing darker candidates with natural hairstyles (Lemi and Brown 2019). They found that hair texture played a particularly important role in the evaluation of Black women candidates (Lemi and Brown 2019). These findings make clear that the body politics for Black women leaders in formal politics are anything but inconsequential and permeate the lived experiences of Black women in office and the kind of support they expect to receive. Our project expands this research to the study of social movements. Specifically, in our research and in this brief, we interrogate the relationship between skin color, hair texture, and evaluations of Black women as social movement leaders.

The Face of a Movement Overview

Within movements created by Black women, Black women are least likely to be chosen to represent them. In a 2017 survey of 815 respondents conducted by the Center for the Study of Diversity and Democracy (CSDD), 27% of respondents chose Colin Kaepernick as whom they want to lead a national Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement. Kaepernick, an American civil rights activist suspended from the NFL San Francisco 49ers after kneeling during the national anthem, was the obvious favorite amongst poll respondents, with Black women BLM co-founders Alicia Garza receiving 10% and Patrisse Cullors receiving 4%.

As social movements and grassroots mobilization become increasingly essential to American politics, studying the identities and bodies individuals choose to center as leaders of these movements becomes materially and politically important.

In this brief, we use a survey to investigate the characteristics most valued in social movement leaders. Then, we examine the influence of phenotypical differences on evaluations of Black women social movement leaders. Our survey design places a premium on the level of “pro-Blackness” that is assumed and how this measure can impact evaluations of Black women’s leadership capabilities in gendered and racialized movements. We find:

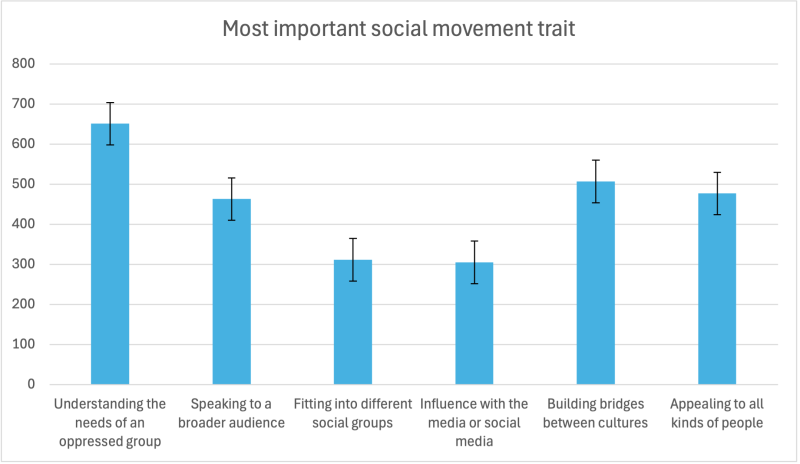

- Respondents rate “understanding the needs of an oppressed group” and “building bridges between cultures” as the most valued traits in social movement leaders.

- Black respondents were the most likely to value social movement leaders’ empathy to the needs of oppressed groups. And while it was still their top-rated trait, white respondents were the least likely among all racial/ethnic groups to rate understanding the needs of an oppressed group as the most important trait of social movement leaders.

- In racial justice movements, Black women with darker skin and natural hair face less negative evaluation than Black women with lighter skin and straight hair.

- In gender-focused movements like #MeToo, Black women leaders overall received more lukewarm and negative ratings than they did strong support, regardless of their physical appearance.

- The same physical features (skin tone, hair type) can help or hurt a Black woman leader's evaluation depending on whether she's leading a racial or gender justice movement.

Data and Method

To understand how Black women leading social movements are evaluated, we first had to study if different leadership traits are required in social movement organizing distinct from running for office. Six key leadership traits emerged from our review of literature on social movements. Each of these traits were characterized in more direct terms in our survey (bolded below). They include:

- Understanding the needs of an oppressed group: Characterized as localized cultural capital in social movement literature, this trait indicates that a leader has deep ties and understandings of the community they represent.

- Speaking to a broader argument: Characterized as universalistic cultural capital in social movement literature, this trait indicates that a leader has knowledge and experience of the workings of the larger public.

- Fitting into different social groups: Characterized as transcultural skills in social movement literature, this trait indicates that a leader can operate in multiple spaces, marginalized and majority.

- Influence with the media or social media: Characterized as weak ties in social movement literature, this trait indicates that a leader has influence within the media, large networks, or communications avenues.

- Appealing to all kinds of people: Characterized as network centrality in social movement literature, this trait indicates that a leader has a position of centrality within the “network.” In this case, the network can be identified as the broad base of the movement in question.

- Building bridges between cultures: Characterized as social brokerage in social movement literature this trait indicates that a leader can connect disparate actors and bridge social gaps.

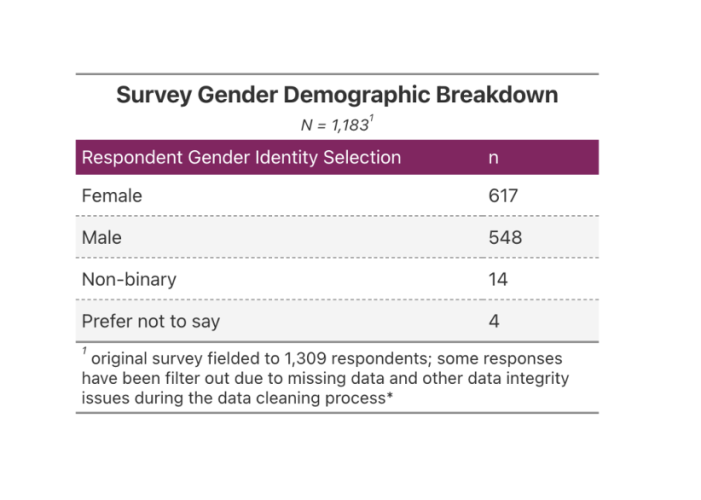

In our survey experiment, we asked respondents (n = 1,183) “What skills are most important for a social movement leader?” and instructed them to rate these leadership traits from 1 to 6, with 1 being the “most important” and 6 being the “least important.” A full demographic breakdown of our survey respondents is below.

To investigate bodily characteristics as potentially related to the invisibility often experienced by Black women in social movements and political leadership, we randomly assigned survey respondents with fictional Black women leaders that varied in their skin tone and hair style.

Each survey respondent evaluated a Black woman leader that either has a dark skin tone + afro, a dark skin tone + straight hair, a light skin tone + straight hair, and a light skin tone + afro hair. The faces were generated using software by the Face Lab, and hair textures were manipulated using Adobe Stock photos. Each leader's profile was accompanied by the same short excerpt, which includes her experience as an organizer and her advocacy for “women’s equal pay” policies and “...to end stop-and-frisk policies that criminalize Black men.”

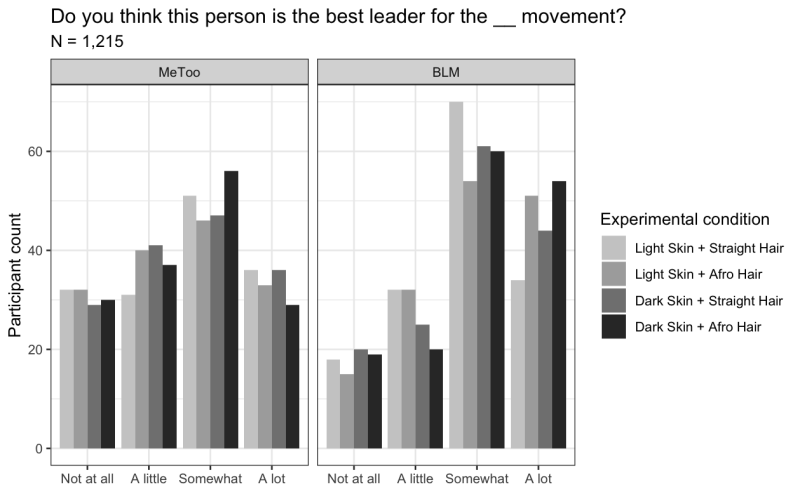

Respondents were then prompted to answer questions about these fictional Black women leaders’ warmth, work ethic, passion, and leadership skills, including asking respondents if they believed that leader “...is the best leader for the [(#Metoo/BlackLivesMatter)] movement.”

To ensure accurate measurements, external validity, and limiting confounders, we ran a pilot in 2021 of our experiment in a large Midwestern university subject pool. We ran a revised, finalized survey in the summer of 2024.

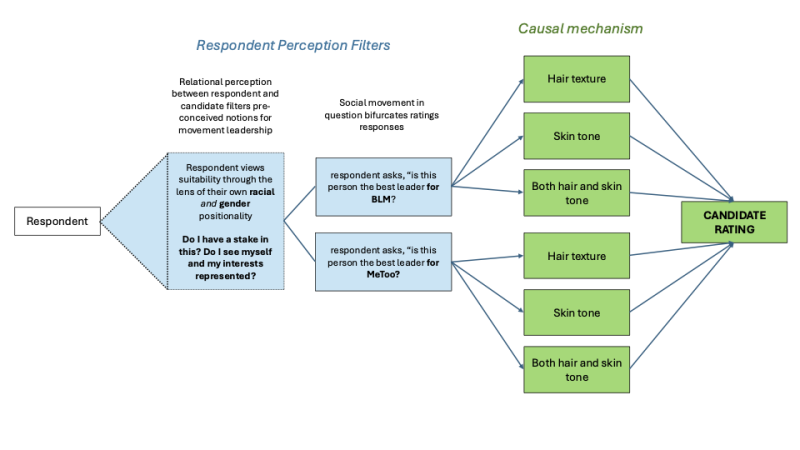

We anticipated that skin tone and hair texture would together influence evaluations of Black women leaders. Previous studies suggest individuals may prefer Black women leaders with lighter skin tones and straight hair. However, in the context of a race-focused movement such as #BlackLivesMatter, we anticipated that Black women with a darker skin tone or Afrocentric hair would receive more favorable evaluations than those with the combination of light skin + straight hair. We argue that either darker skin or Afrocentric hair alone can serve as a visual cue signaling an embodied kinship with the Black experience. Yet, the combination of both phenotypic traits (dark skin + Afro-Centric hair) would challenge norms of professionalism and respectability—producing less favorable ratings.

In contrast, we expected evaluations of Black women leading the #Metoo movement to align most closely to what the literature suggests. Since the #Metoo movements is presumably framed around violence against “women” as a collective subject, which framing has historically stifled racial difference, we anticipated evaluations to favor leadership that embodies proximity to whiteness.

The chart below shows how we interpret the movement in question and Black women's phenotypes to affect leader ratings.

Results

Valued Leadership Traits of Social Movement Leaders

We found that the social movement trait that was the most important to our respondents was “understanding the needs of an oppressed group,” with over 45% of respondents ranking this as their number one. “Building bridges between cultures” was ranked the second most important trait, with about 30% of respondents considering this their most important trait and almost 20% ranking it as their second most important trait. The data suggests that “influence with the media or social media” is the least essential trait amongst participants, with “fitting into different social groups” coming in second to least important.

Source: Original prime panel study ran in April of 2024 (n= 1,183)

The low rating of media/social media influence is interesting, as social media played a crucial role in the Black Lives Matter movement and #Metoo. When we stratified the data by race, we found more enthusiasm for leaders having “influence with the media or social media” from Latino and Black Americans especially, with the least enthusiasm from white Americans.

When breaking down all responses by racial and ethnic group and then normalizing the results by racial group size, we see more interesting trends. For instance, although “understanding the needs of an oppressed group” was the most highly rated trait overall, white respondents rated this characteristic, and all other social movement traits, lower than respondents from other racial groups. The largest disparities appeared in ratings for “speaking to a broader audience” and “influence with the media.” Latino respondents rated “influence with the media” higher than all other groups, which may reflect the role of social media in shaping immigration discourse and/or negative portrayals of Latinos (Chavez 2013; Santa Ana 2002). Similarly, Native American or Indigenous respondents’ emphasis on “speaking to a broader audience” may reflect ongoing concerns about the marginalization and erasure of Native voices in mainstream political discourse (Lavelle, Larsen and Gundersen 2009; Sanchez & Foxworth 2022).

These initial analyses showcase how racial groups and their respective experiences navigating inequality in the United States could potentially result in different evaluations of social movement leadership characteristics.

Phenotype Influence on Social Movement Leader Evaluation

Our study found striking differences in how people evaluate Black women leaders based on the type of movement they lead. We studied how people respond to political messages (BLM or MeToo) when they come from people with different physical appearances. We looked at eight different combinations of skin tone, hair type, and political message.

To understand our ordinal logistic regression results, we compared all combinations to one baseline group: Black women with dark skin and afro hair supporting BLM. Think of this as our “starting point” for comparison. We chose this condition as the one to compare other impressions with because it is “on paper” the combination of traits that we believed respondents would expect a leader of a pro-Black movement to have: dark skin and afro-hair, both representing greater degrees of “Blackness” in appearance. This means that the results for other conditions and leader traits are compared against this ideal case, so to speak. When evaluating a Black woman with dark skin and afro hair for MeToo, respondents tended to support this woman less than her dark skin, afro hair and BLM counterpart. Likewise, evaluations for a leader with light skin and afro hair leading MeToo received less favorable ratings than our dark skin, afro hair, BLM leader baseline.

Table 1: Ordinal Logistic Regression Results

We found that for the #MeToo movement, Black women consistently received lower ratings as potential leaders, regardless of their appearance, than they did leading BLM movements. The ratings were so consistently low that a Black woman leader in #MeToo was about half as likely to receive high ratings compared to our baseline expectations (dark Skin + afro Hair + BLM). This was true whether the leader had light or dark skin, or straight or natural hair.

The pattern is different for Black Lives Matter (BLM) leaders. Here, a leader's appearance played a bigger role in how they were evaluated. Black women with dark skin and natural hair received more favorable ratings (of “somewhat” or “a lot”) as potential leaders for BLM than they did as #MeToo leaders.

While #MeToo ratings show little variation based on appearance, BLM ratings show more preference for leaders whose appearance aligned with traditional Black features. However, in both movements, respondents tended to choose middle-ground ratings ("somewhat") more often than strong positive or negative ratings.

Key Differences:

- Among Black women #MeToo leaders, appearance variations had minimal impact. All Black women leaders faced similar barriers.

- Among Black women BLM leaders, traditionally Black features (dark skin, afro hair) aligned with highest leadership ratings.

- The combination of light skin and straight hair appear least likely to evoke strong favorable convictions in BLM leadership evaluation.

- Dark skin + afro hair appear as the most positively evaluated combination for BLM, while being among the lowest rated under “A lot” for #MeToo.

Additional statistical tests detailed in the tables below demonstrate that Black women with dark skin and afro hair who lead BLM movements are, overall, the most likely to be viewed with certainty as the best leader for their movement. Their advantage among Black women BLM leaders with other phenotype combinations is either weak or non-significant, but they are rated significantly higher as movement leaders than Black women #MeToo leaders with any skin and hair type combination. More detailed comparisons show that:

- A Black woman with light skin and afro hair faced the least positive ratings as a #MeToo leader. She was 56% less likely to receive the highest rating as a movement leader than a Black woman with dark skin and afro hair who was a BLM movement leader.

- The same combination – light skin and afro hair – was rated closest (only 11% less likely to receive the highest rating as movement leader) to a Black woman with dark skin and afro hair when both were evaluated as BLM movement leaders.

Table 2: Odds Ratios for Each Condition

Table 3: Predicted Probabilities of Ratings by Condition

To summarize:

Physical features commonly associated with Blackness – like dark skin and afro-textured hair – are viewed more positively in Black women in leadership of a Black-centered movement (BLM). In contrast, for the gender-focused #MeToo movement, all Black women face similarly strong negative evaluations regardless of their appearance, with ratings consistently about 50% lower than Black women with dark skin + afro hair combination leading racial justice movements.

For #MeToo, this is particularly troubling since Black women founded and sustain many gender justice movements and results suggest deep-rooted resistance to Black women's leadership in gender-focused movements.

Implications

These findings matter for several reasons:

- Movement organizations need to actively fight against biases that limit Black women's leadership opportunities, especially in gender-focused movements.

- We need to pay attention to how skin tone bias and racism work together to affect leadership opportunities in different types of movements.

- The fact that Black women are consistently undervalued as leaders, even in movements they started, shows we need major changes in how movement leadership is recognized and supported.

Michelle Bueno Vásquez is a PhD candidate in Political Science at Northwestern University. She can be reached at michellebuenovasquez2024@u.northwestern.edu. Andrene Z. Wright-Johnson is an Associate Professor of Political Science at University of Wisconsin-Madison. She can be reached at azwright@wisc.edu.

Suggested Citation: Bueno Vásquez, Michelle A., and Andrene Z. Wright-Johnson. 2025. "The Face of a Movement: Colorism and Racism in the Evaluation of Black Women Leaders." Center for American Women and Politics, Eagleton Institute of Politics, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ.

1 Gill, Gurvinder, and Imran Rahman-Jones. 2020. “Me Too Founder Tarana Burke: Movement Is Not Over.” BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/newsbeat-53269751 (March 18, 2021).

2 “ 'Our Pain Is Never Prioritized.’ #MeToo Founder Tarana Burke Says We Must Listen to ‘Untold’ Stories of Minority Women.” 2019. Time. https://time.com/5574163/tarana-burke-metoo-time-100-summit/ (March 18, 2021).

References

Brown, N. E., & Lemi, D. C. 2020. “‘Life for Me Ain't Been No Crystal Stair:’ Black Women Candidates and the Democratic Party.” BUL Rev., 100, 1613.

Buchanan, L., Bui, Q., & Patel, J. K. 2020. “Black Lives Matter May Be the Largest Movement in US History.” The New York Times, 3(07).

Chavez, L. 2013. “The Latino Threat: Constructing Immigrants, Citizens, and the Nation.” In The Latino Threat. Stanford University Press.

Edrington, C. L., & Lee, N. 2018. “Tweeting a Social Movement: Black Lives Matter and Its Use of Twitter to Share Information, Build Community, and Promote Action.” The Journal of Public Interest Communications, 2(2), 289-289.

Ince, J., Rojas, F., & Davis, C. A. 2017. “The Social Media Response to Black Lives Matter: How Twitter Users Interact with Black Lives Matter Through Hashtag Use.” Ethnic and Racial Studies, 40(11), 1814-1830.

Jaffe, S. 2018. “The Collective Power of #MeToo.” Dissent, 65(2), 80-87.

Jones, L. K. 2020. “#BlackLivesMatter: An Analysis of the Movement as Social Drama.” Humanity & Society, 44(1), 92-110.

Lavelle, B., Larsen, M. D., & Gundersen, C. 2009. “Strategies for Surveys of American Indians.” Public Opinion Quarterly, 73(2), 385-403.

Lemi, D. C., & Brown, N. E. 2019. “Melanin and Curls: Evaluation of Black Women Candidates.” Journal of Race, Ethnicity, and Politics, 4(2), 259-296.

Leopold, J., Lambert, J. R., Ogunyomi, I. O., & Bell, M. P. 2021. “The Hashtag Heard Round the World: How# MeToo Did What Laws Did Not.” Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal, 40(4), 461-476.

Mundt, M., Ross, K., & Burnett, C. M. 2018. “Scaling Social Movements Through Social Media: The Case of Black Lives Matter.” Social Media + Society, 4(4).

Nepstad, S., & Bob, C. 2006. “When Do Leaders Matter? Hypotheses on Leadership Dynamics in Social Movements.” Mobilization: An International Quarterly, 11(1), 1-22.

Nummi, J., Jennings, C., & Feagin, J. 2019. “#BlackLivesMatter: Innovative Black Resistance.” Sociological Forum, 34, 1042-1064.

Sanchez, G. R., & Foxworth, R. 2022. “Social Justice and Native American Political Engagement: Evidence from the 2020 Presidential Election.” Public Opinion Quarterly, 86(S1), 473-498.”

Santa Ana, O. 2002. Brown Tide Rising: Metaphors of Latinos in Contemporary American Public Discourse. University of Texas Press.

Tillery, A. B. 2017. “How African Americans See the Black Lives Matter Movement.” Center for the Study of Diversity and Democracy Poll.

Appendix