What makes a political candidate likable? In any competitive election, voters are faced with a choice between multiple candidates whom they are asked to learn about, form opinions of, and choose between. In this process, there are certain attributes that candidates are typically evaluated on, including things like their policy stances, partisanship, and personality traits. Included among these considerations is often the rather nebulous concept of how ‘likable’ a candidate is — sometimes colloquially thought about as whether you’d like to ‘have a beer’ with the candidate or not. However, although it is a common assumption that likability is an important factor in the candidate evaluation process, there is little scholarly agreement on what exactly it means to be likable in a political context or how important it really is to voters.

At the same time, likability seems to be a concept that is gendered in various ways. Even the ‘beer test’ mentioned above has gendered connotations. Research from psychology shows that people generally find those who are warm, agreeable, and friendly more likable in interpersonal relationships (Anderson 1968; Jensen-Campbell et al. 2002). Yet in leadership contexts, where more masculine traits like competence and assertiveness are valued, these dynamics can interact with gender stereotypes and women candidates may be particularly vulnerable to likability-based critiques. Research on the ‘double-bind’ suggests that women who run for political office may face a trade-off between competence/leadership and likability, as women are expected to possess feminine traits to be likable while leaders are expected to possess masculine traits. This can lead voters to see women candidates as either not ‘masculine enough’ to be leaders or not ‘feminine enough’ to be likable as women (e.g. Eagly and Karau 2002). Heilman & Okimoto (2007), for example, show how successful women in leadership roles who exhibit assertiveness are perceived as competent but less likable, thus incurring social penalties, while Bauer (2017) finds that women candidates face a likability backlash specifically from members of the opposing political party. These penalties are compounded for women of color, who must navigate stereotypes tied to both gender and race (e.g. Hancock 2007; Gershon and Monforti 2021).

Taken together, this scholarship suggests that likability is both consequential and gendered. Yet despite its ubiquitousness in media coverage and polls during campaign seasons, likability remains conceptually underdeveloped and the key factors that lead a candidate to be seen as likable are poorly understood and tested, as is its role in determining vote choice. This leaves an important deficit in existing candidate evaluation research, which then carries over to actual campaigns, leaving real-world candidates with little guidance as to how to navigate perceptions of likability (and whether this is even something worth worrying about). This project seeks to fill that gap by investigating what makes candidates seem likable to voters, and how gender, alongside other important attributes like race and partisanship, shape these perceptions.

To summarize our findings, our results suggest that:

- women are perceived as more likable than men when evaluated as ‘regular’ people;

- women lose any likability advantage over men when evaluated as political candidates;

- women participants find women candidates to be more likable than men and men find women candidates to be less likable than men, revealing how shared gender identity seems to influence candidate evaluations;

- there is a partisanship effect in which Democrats tend to find women candidates more likable and Republicans tend to find women less likable;

- women of color are not seen as less likable than white women, but some men of color are seen as less likable by some groups of voters;

- candidates who are outgoing, sympathetic, and dependable are seen as more likable; and

- candidates with children are seen as more likable than those without.

Research Approach

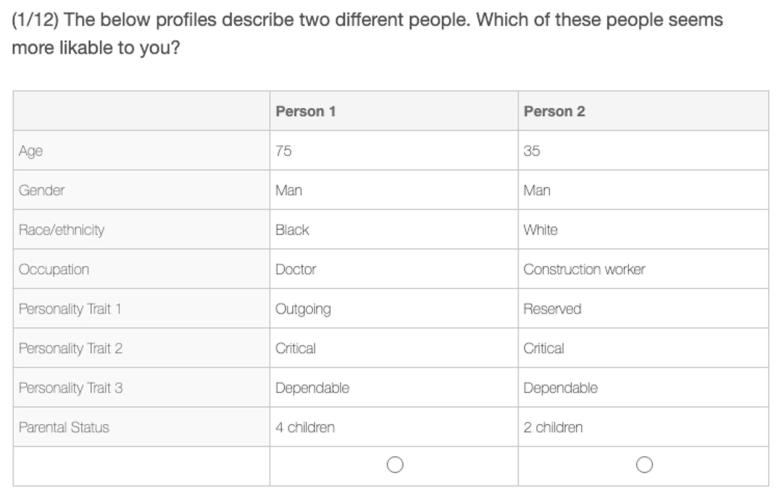

To investigate how likability judgments are formed, we conducted a series of forced-choice conjoint experiments with a total of 2,000 participants. Experiment participants were recruited from an online sample of U.S. citizens aged 18 and above. In these studies, participants were asked to view a series of pairs of person profiles and then to determine which profile they found more likable. Participants were randomly assigned to one of five different groups. In one, they were asked to evaluate pairs of profiles as if they were ordinary people (i.e. they were not told they were evaluating political candidates). In the remaining groups, participants were asked to evaluate the same profiles as if they were political candidates running in one of four different elections. In these groups, participants were asked to evaluate candidates for either their local school board, the House of Representatives, their state governor, or president. In all cases, participants were instructed that the candidates they were evaluating were running within their own political party (i.e. in a primary election).

Each pair of profiles included information about the target individuals’ gender, race/ethnicity, age, occupation, parental status, and personality traits. These attributes were randomly varied across profiles, allowing us to see how each influenced perceptions of likability. In particular, we focused on how gender and its interaction with other attributes shaped voters’ judgments.

We analyzed our data using marginal means, which estimate the average likelihood that someone with a particular characteristic – such as a certain gender, race, or age – was rated as more likable than the other profile they were evaluated against. In other words, the results tell us the overall chance that a person with each trait would be chosen as more likable, averaging across all the other information people saw. Each dot in the figure represents the average likelihood for one version of an attribute (for example, being a man or a woman in the ‘gender’ category) on a 0-1 scale. The higher the dot, the more often people with that characteristic were rated as likable. In practical terms, these can also be read as percentages showing how often people with each trait were chosen as the more likable option. For instance, non-political profiles described as women were selected as more likable about 51% of the time, compared to 49% for men. The horizontal lines around each dot show how certain we are about those results — the shorter the line, the more confident we can be. If the lines from two dots overlap, it means their difference is probably not large enough to be meaningful. The figure also uses two colors: blue for ratings of regular people and red for political candidates. All the figures in this report are presented in essentially the same format.

Figure 1. Example of decision task for respondents in the “non-political’ condition

Findings

People vs. Politicians

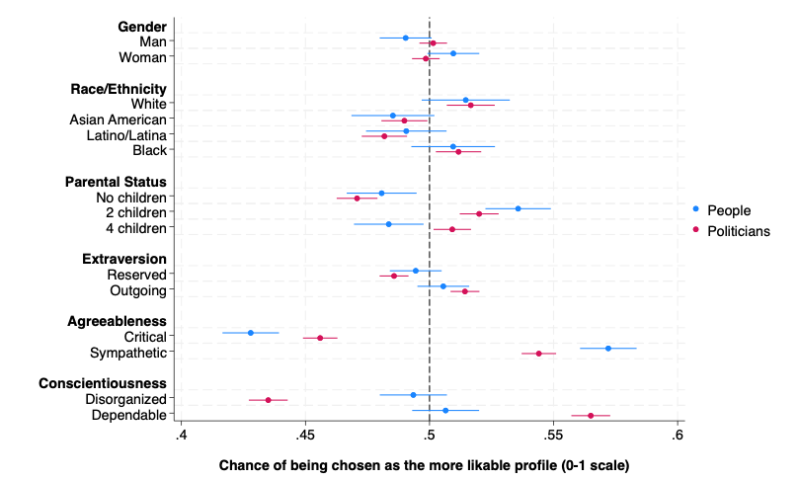

We begin by looking at the overall differences in evaluations when participants were asked to evaluate ‘regular’ (non-political) people vs. political candidates (Figure 2).

A few patterns emerge from these findings. The first is that women are perceived differently depending on whether they are judged as ordinary people or as political candidates. When participants evaluated people in general, women were rated as more likable slightly more often than men were (51% of the time compared to 49% of the time). Yet, when these same profiles were framed as political candidates, women lost this two-point advantage and were evaluated as equally likable to men. This suggests that any likability benefits women may enjoy in everyday life do not carry over into politics. This may be because the role of candidate is still associated with masculinity, which undermines women’s ability to translate everyday perceptions of warmth into political capital.

Figure 2. Probability of being rated as more likable: Non-political person vs. political candidate

Parenthood also shaped perceptions of likability. Candidates with children were generally more likely to be viewed as likable than those without, as candidates with both two and four children had a higher chance of being seen as likable than did childless candidates (there is a five-point difference between those with two children and those with none, for example). Interestingly, while politicians with four children were more likely to be seen as likable (by four percentage points), regular people with four children were not. Importantly, expectations around parenthood tend to place greater burdens on women, who are often judged not only on their professional competence but also on whether they fulfill conventional family roles.

Race and ethnicity also influenced perceptions of likability for political candidates, but not for non-political people. Asian American and Latino/a/x candidates were three and four percentage points (respectively) less likely to be seen as likable than white candidates, while Black candidates were statistically just as likely as white candidates to be chosen as likable. Further, subgroup analyses (not shown) reveal that both white and Black respondents tended to prefer candidates from their own racial group. These results highlight how likability is not a universal attribute but is filtered through individual identities such as race and gender.

Across all conditions, personality traits had some of the strongest effects on likability. Candidates described as sympathetic (54%), dependable (57%), and outgoing (51%) were consistently more likely to be chosen as likable than were those described as critical (46%), disorganized (44%), or reserved (49%). These penalties were especially sharp when compared to the results for non-political people. In politics, failing to meet expectations of warmth and dependability may be especially costly, and women candidates may face harsher scrutiny for perceived shortcomings in these areas due to the double bind.

Gendered Differences in Evaluations – Comparing Men and Women’s Profiles

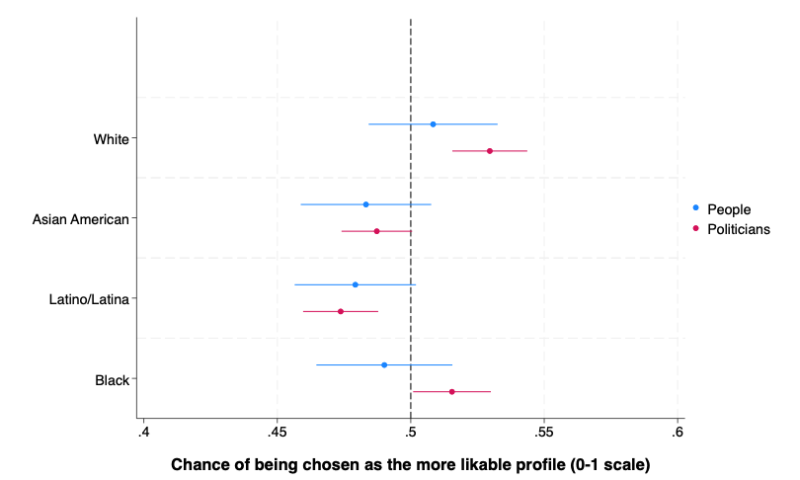

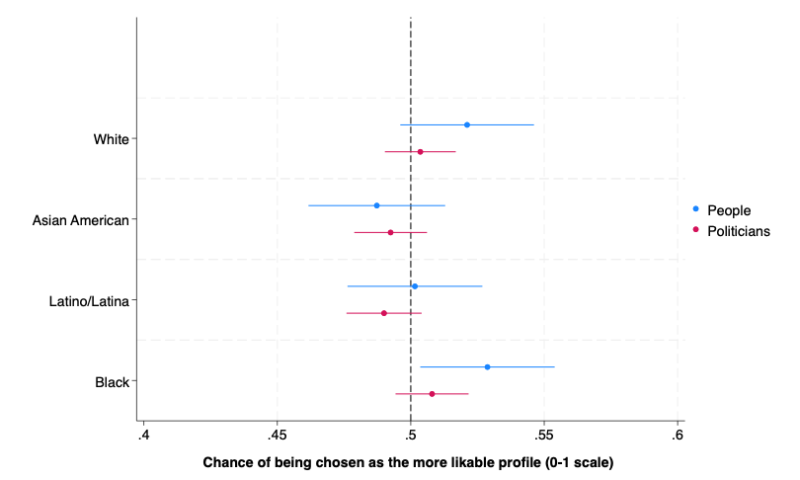

We also looked to see whether likability ratings across other dimensions were different when participants evaluated men vs. women. Figure 3 shows the marginal means for participants evaluating men as ordinary people or politicians, and Figure 4 shows the marginal means for participants evaluating women as ordinary people or politicians. In general, many of the variables in our study function similarly in terms of how they affect likability for both men and women but there do seem to be some notable differences in terms of race and ethnicity. Asian American and Latino men politicians (Figure 3) are seen as likable less often than white and Black men politicians (by 3-4%, though the same is not true for non-political people). For Asian American and Latina women, however, we do not see the same disadvantage. There don’t seem to be any statistically significant differences in likability evaluations for women of different racial or ethnic groups in our study. In this instance, it is only male Asian American and Latino candidates who seem to be disadvantaged in terms of likability based on racial/ethnic identity.

Figure 3. Probability of being rated as more likable: men’s profiles

Figure 4. Probability of being rated as more likable: women’s profiles

Gendered Differences in Evaluations – Comparing Men and Women Participants

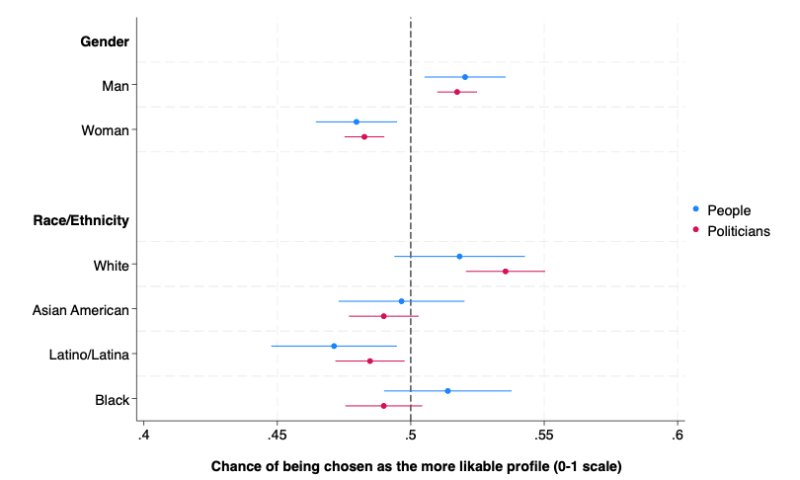

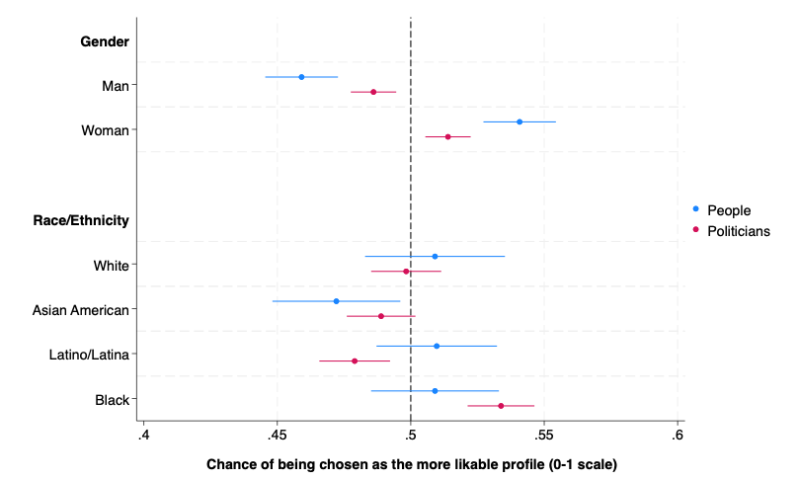

We also consider differences between men and women participants in the study (Figures 5 and 6). In other words, did men and women who took our study differ in the attributes they found likable? Generally, the answer is no, but there are a few important differences. First, men were more likely to rate white politicians as likable than candidate profiles of any other racial or ethnic group. Women, on the other hand, most often found Black politicians to be more likable than politicians from other racial or ethnic groups.

Figure 5. Probability of being rated as more likable: men participants’ responses

Figure 6. Probability of being rated as more likable: women participants’ responses

There is also a noticeable difference in terms of how men and women participants evaluated the likability of men and women targets. Men found both non-politician women and women candidates to be likable less often than men in these categories. Women, on the other hand, found women in both categories to be likable more often. This is especially true with regard to women as ordinary people. This speaks to the importance of similarity in evaluations of likability. Prior research has found that people tend to find others more likable if they have some characteristics in common. Our study confirmed this tendency: respondents were generally more likely to find someone likable if they had something in common with them. However, this effect was weaker in the ‘political candidate’ condition than in the ‘people’ condition for women participants, suggesting that similarity may matter more when evaluating people in everyday life than when thinking about politicians. This may be because the mental image of a typical politician is still often a man for many voters, or it may be because of the scrutiny around likability that is often leveled at women who run for high-level political office.

Partisan Differences in Likability Evaluations

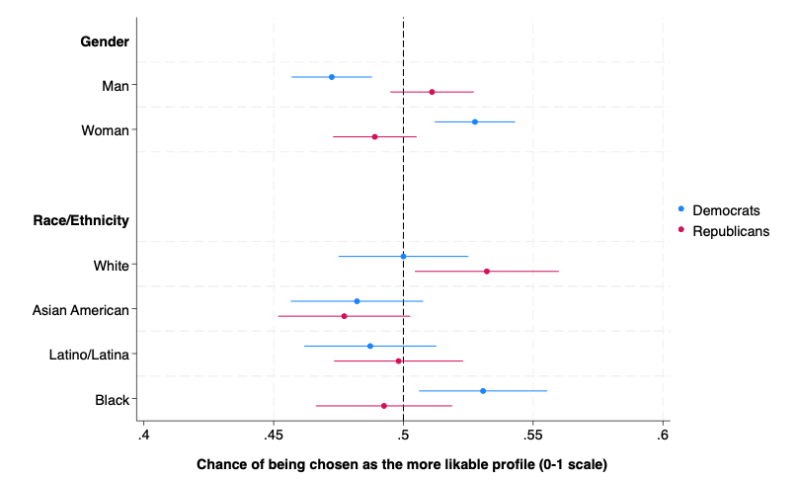

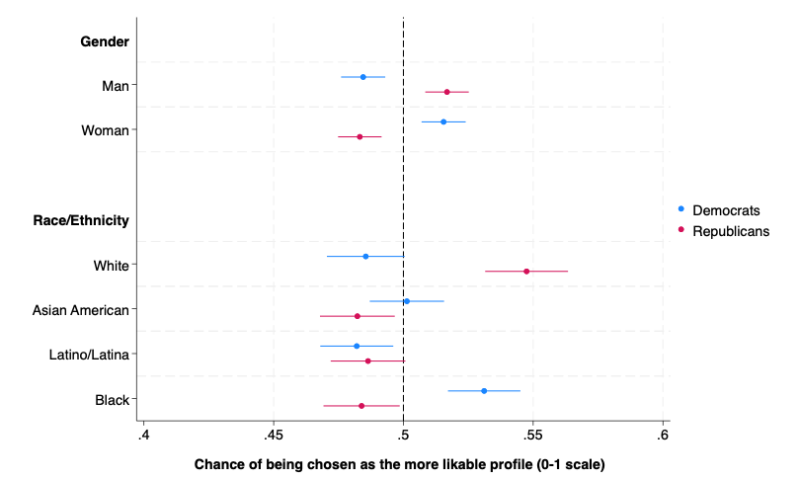

Finally, we consider differences in likability ratings by the partisanship of the participants in the study. Figure 7 shows ratings for non-political people and Figure 8 shows results for political candidates. There are clearly partisan differences in terms of how Democrats and Republicans evaluate the likability of political candidates in terms of their gender and their race/ethnicity. Democrats seem to find women candidates more likable than men candidates, while Republicans are less likely to evaluate women candidates as likable than they are men candidates. Democrats are also more likely to find Black candidates more likable than candidates of other racial or ethnic groups, while Republicans are more likely to see white candidates as more likable.

Figure 7. Probability of being rated as more likable for non-political people by participant partisanship

Figure 8. Probability of being rated as more likable for political candidates by participant partisanship

Conclusion and Next Steps

Taken together, these findings highlight the nuanced nature of likability evaluations and suggest that they are dependent on gender, race, and partisanship, among other things. Our research underscores that likability is not simply a matter of personal charm. It reflects entrenched social expectations about gender, race, and leadership. For women, likability can become another barrier to success in politics, depending on the party and office in question, as well as the gender of the voters doing the evaluating. Gender likely plays a further indirect role in that parental status and personality traits, two deeply gendered phenomena, are also important predictors of likability.

There are many possible directions for future research on candidate likability, including the extent to which likability influences vote choice, how media portrayals reinforce or challenge these dynamics, and how women candidates strategically present themselves to navigate these perceptions. These questions are crucial not only for understanding voter behavior but also for advancing the representativeness of our political institutions.

This study also highlights several important considerations for candidates, campaign teams, and those working to improve gender representation in politics.

- First, women are generally seen as more likable than men, but this advantage disappears when they run for office, highlighting persistent double standards in perceptions of leadership. This suggests that likability changes based on the role or context in which someone is being evaluated. Women’s likability (or lack thereof) isn’t universal but depends on the circumstances in which the evaluation is taking place.

- Second, likability judgments are shaped by voters’ own identities and partisanship. Women voters tend to view women candidates more favorably, while men are less likely to do so, indicating that shared identity and gender bias both influence evaluations. Likewise, Democrats tend to rate women candidates as more likable, while Republicans are less favorable — showing that the same candidate may face very different receptions depending on the partisan makeup of the audience. Understanding these patterns can help campaigns tailor their messaging, tone, and outreach to specific constituencies.

- Third, our findings offer encouraging news regarding women of color, who are rated as similarly likable to white women overall. However, some men of color face steeper likability barriers, which points to the need for intersectional awareness in candidate support and training efforts for men candidates as well as for women.

- Finally, candidates who are parents tend to be viewed as more likable, probably reflecting persistent cultural expectations that link family life with warmth and relatability. Campaigns can consider ways to highlight these personal dimensions authentically, without reinforcing outdated gender norms or family stereotypes.

Tessa Ditonto is an Associate Professor of Gender and Politics at Durham University. David Andersen is an Associate Professor in United States Politics at Durham.

Suggested Citation: Ditonto, Tessa and Andersen, David. 2025. "Gender and Candidate Likability." Center for American Women and Politics, Eagleton Institute of Politics, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ.

References

Anderson, N.H., 1968. Likableness ratings of 555 personality-trait words. Journal of personality and social psychology, 9(3), p.272.

Bauer, N.M., 2017. The effects of counterstereotypic gender strategies on candidate evaluations. Political Psychology, 38(2), pp.279-295

Eagly, A.H. and Karau, S.J., 2002. Role congruity theory of prejudice toward female leaders. Psychological review, 109(3), p.573

Gershon, Sarah Allen and Jessica Lavariega Monforti. 2021. Intersecting campaigns, candidate race, ethnicity, gender and voter evaluations. Politics, Groups, and Identities 9(3), p. 439-463.

Hainmueller, J, Hopkins, D, Yamamoto, T. 2014. Causal inference in conjoint analysis: Understanding multidimensional choices via stated preference experiments. Political Analysis. 22(1): 1-30. Doi: 10.1093/pan/mpt024

Hancock, A.M., 2007. When multiplication doesn't equal quick addition: Examining intersectionality as a research paradigm. Perspectives on politics, 5(1), pp.63-79.

Heilman, M.E. and Okimoto, T.G., 2007. Why are women penalized for success at male tasks?: the implied communality deficit. Journal of applied psychology, 92(1), p.81.

Jensen-Campbell, L. A., Adams, R., Perry, D. G., Workman, K. A., Furdella, J. Q., & Egan, S. K. (2002). Agreeableness, extraversion, and peer relations in early adolescence: Winning friends and deflecting aggression. Journal of Research in Personality, 36, 224–251. doi:10.1006/jrpe.2002.2348