Intersectionality in User Replies to Congressional Candidates’ Tweets

An increasing number of politicians report being targets of harassment, abuse, and misinformation campaigns on social media platforms. Women of color in politics, in particular, have become usual targets of harassment and abuse in social media. Do women and people of color in politics indeed face hostile attacks from social media users more often than others?

In an analysis of Twitter replies to major-party general election candidates for the U.S. House in 2020, I find:

- White women candidates on average receive replies that are less toxic than white men candidates. This pattern may be driven by gendered differences in content of candidates’ tweets and calls for more in-depth research on women candidates’ social media communication styles.

- However, there are considerable racial differences in the toxicity of replies that candidates receive. Black women receive more toxic replies than Black men. Latina candidates receive equally toxic replies as Latino candidates. This finding calls for an intersectional approach to online violence against candidates.

How did we do our research?

I collected Twitter replies to 557 major-party general election candidates in the 2020 election for the U.S. House of Representatives from August 3 to November 3, 2020.1 This includes all major-party U.S. House candidates who had a Twitter account, posted tweets during this period, and whose tweets received any public replies. The vast majority of candidates included are male and are white, consistent with the full population of major-party general election House candidates.

This study limits the analysis to textual content, thus, tweets containing only links, emojis, images, or videos are excluded. The final dataset used for analysis consists of 434,599 replies to 50,356 original tweets.2 Using this original data set of voter-candidate social media interactions, I measured the toxicity of public replies to candidates using the Perspective API, a machine learning model that identifies aggressive and hateful comments. The perspective API analyzes text input and provides a toxicity score, indicating the probability that the text contains language that could be considered toxic. While it provides toxic scores for six different attributes - toxicity, severe toxicity, identity attack, insult, profanity, and threat – I focus on the primary measure of toxicity. Toxicity is defined in this model as “a rude, disrespectful, or unreasonable comment that is likely to make people leave a discussion.”

Results

In my analysis, I use OLS regression to evaluate the relationship between candidate gender, race/ethnicity, and the level of toxicity in replies to their tweets. I also include a measure for the interaction of gender and race/ethnicity to determine the degree to which these identities function together to predict toxicity in replies.

I find that female candidates for the U.S. House in 2020 were less likely to receive toxic or hostile replies from Twitter users than male candidates across all types of toxicity scores. Second, racial and ethnic minority candidates received more toxic replies than white candidates. Finally, and most importantly, the results suggest that being a minority female candidate jointly increases the levels of toxicity in Twitter replies. Models include control variables such as party affiliation, incumbency, and whether the candidate competed in an open-seat race. In these analyses, “minority” indicates the replies sent to the tweet of a non-white candidate.

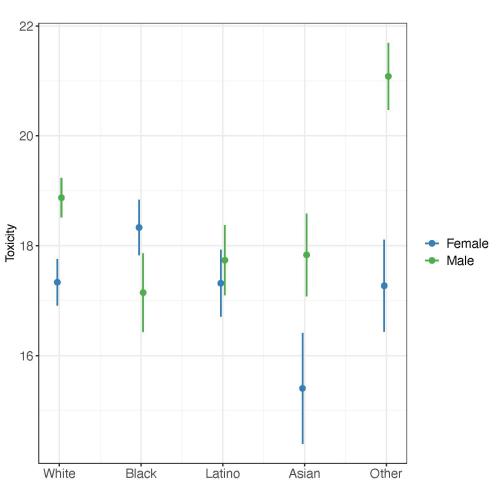

Predicted Values of Toxicity Score by Candidate Race and Gender

The figure below plots the predicted toxicity scores based on the regression estimates, holding the values of the control variables at their means or medians, by candidate gender and minority status. It shows that the likelihood of receiving toxic replies is actually less for white women than white men. However, the likelihood of toxic replies appears to be about the same for minority women and men, both higher than white candidates.

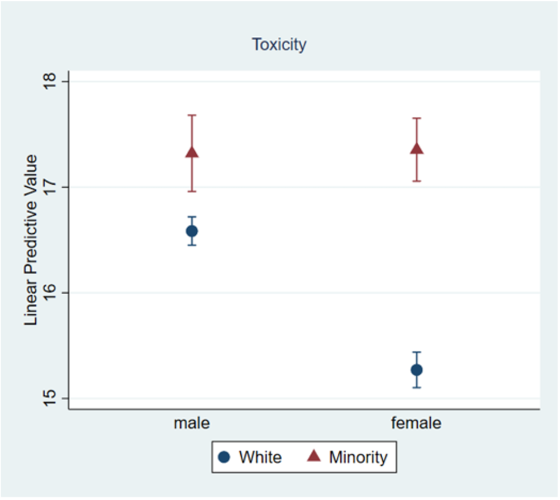

Predicted Values of Toxicity Score by Candidate Race (Combined) and Gender

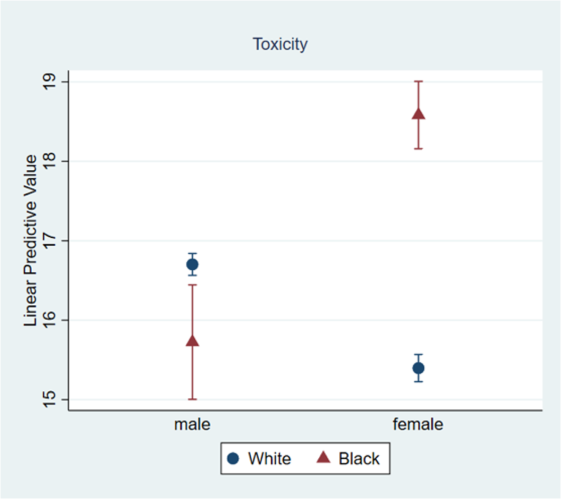

Next, I compare replies that Black candidates received with those received by white candidates. The results show that Black women candidates receive the most toxic replies, followed by white men, Black men, and white women candidates. While white women candidates receive less toxic replies than their male counterparts, replies that Black women candidates received were much more hostile replies than Black men candidates.

Comparison of Predicted Toxicity Scores Between Black and White Candidates and by Gender

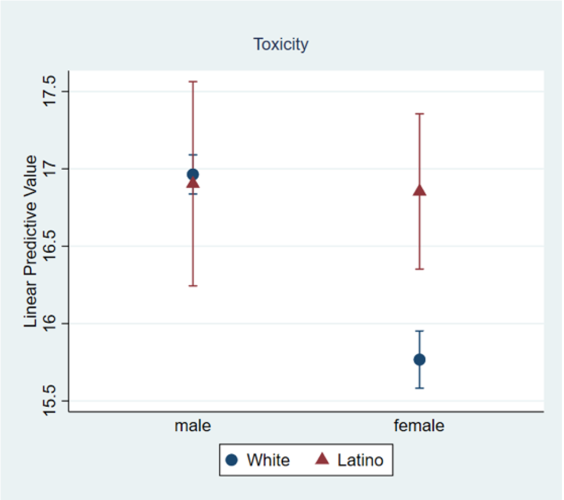

Somewhat different patterns of intersectionality appear when I focus on Latino candidates. My findings suggest that while white women candidates tend to receive toxic replies less frequently than white men, Latina candidates are equally likely to receive toxic replies as Latino candidates.

Comparison of Predicted Toxicity Scores Between Latina/o and White Candidates and by Gender

Implications

My findings first suggest that on average, men candidates are more frequently subject to hostile replies on social media than women candidates. These finding contradict previous research, which suggests that women politicians are more frequent targets of violence and abuse than men politicians.3 I suspect that my finding may be driven by gender differences in content of tweets. Studies show that women politicians tend to tweet more about policy issues, while men politicians use more words related to ideology.4 Relatedly, women candidates may be less likely to post about divisive or sensitive topics, and thus, receive hostile replies less frequently than men. In other words, women politicians may be more likely to self-censor their social media posts and avoid inciting toxic communication. I will explore this possibility in my future research.

However, I also find that this gender effect varies considerably depending on the race/ethnicity of the candidate. While white male candidates receive more hostile replies than white female candidates, non-white women receive similar or more hostile replies than non-white men. This finding underscores the importance of an intersectional approach to understanding online political communication and institutional solutions to online attacks against politicians.

Finally, I find that women of color candidates are significantly more likely to receive toxic replies than white women. This tendency is particularly strong when Black women candidates are compared to white women, as demonstrated by the large difference in the predicted toxicity score between the two groups in Figure 2. Future work could further explore how this intersectionality appears differently by the topic of tweets (e.g., policy vs. personal content) or by the type of race.

Jeong Hyun Kim is an Assistant Professor at the Department of Political Science and International Studies at Yonsei University. She can be reached at jhkim1@yonsei.ac.kr.

Suggested Citation: Kim, Jeong Hyun. 2024. "Intersectionality in User Replies to Congressional Candidates’ Tweets." Center for American Women and Politics, Eagleton Institute of Politics, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ.

[1] One Independent candidate, Alyse Gavin (AK), was included.

[2] Data collection was conducted through Twitter’s streaming application programming interface (API), using an open-source Python package.

[3] Krook, Mona Lena. 2018. “Violence against women in politics: A rising global trend.” Politics & Gender 14(4):673–675; Krook, Mona Lena and Juliana Restrepo Sanín. 2020. “The cost of doing politics? Analyzing violence and harassment against female politicians.” Perspectives on Politics 18(3):740–755.

[4] Beltran, Javier, Aina Gallego, Alba Huidobro, Enrique Romero, and LLuís Padró. 2021. “Male and female politicians on Twitter: A machine learning approach.” European Journal of Political Research 60(1): 239-251; Evans, Heather K and Jennifer Hayes Clark. 2016. “ ‘You tweet like a girl!’ How female candidates campaign on Twitter.” American Politics Research 44(2):326–352.

Appendix

Descriptive Statistics of Candidates in the Sample

| Gender | N | Race | N | Age | N | Party | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 186 | White | 440 | 25-34 | 30 | Republican | 267 |

| Male | 371 | Black | 57 | 35-44 | 81 | Democrat | 289 |

| Latino | 33 | 45-54 | 101 | Other | 1 | ||

| Asian | 12 | 55-64 | 132 | ||||

| Other minority | 15 | 65-74 | 102 | ||||

| 75-84 | 23 | ||||||

| 85 or older | 1 | ||||||

| NA | 87 | ||||||

| Sum | 557 |

- 1

One Independent candidate, Alyse Gavin (AK), was included.

- 2

Data collection was conducted through Twitter’s streaming application programming interface (API), using an open-source Python package.

- 3

Krook, Mona Lena. 2018. “Violence against women in politics: A rising global trend.” Politics & Gender 14(4):673–675; Krook, Mona Lena and Juliana Restrepo Sanín. 2020. “The cost of doing politics? Analyzing violence and harassment against female politicians.” Perspectives on Politics 18(3):740–755.

- 4

Beltran, Javier, Aina Gallego, Alba Huidobro, Enrique Romero, and LLuís Padró. 2021. “Male and female politicians on Twitter: A machine learning approach.”European Journal of Political Research 60(1): 239-251;Evans, Heather K and Jennifer Hayes Clark. 2016. “ ‘You tweet like a girl!’ How female candidates campaign on Twitter.” American Politics Research 44(2):326–352.