Colorado is often considered a leader in women’s political representation. In 1893, it became the second state to give women the right to vote, and the following year, it became the first state to elect not one, but three women to serve in the state legislature. Colorado was the second state to reach gender parity in statehouse representation, in 2023, and in 2024, they joined New Mexico and Nevada in reaching majority-woman status.

Not all groups of women, however, have had access to the same political opportunities. The first Latina to serve in the Colorado General Assembly wasn’t elected until 1970, over seventy-five years after the first (white) women were elected. It was also over a century after the first Latino male legislators (then called Hispanos) were elected to the territorial legislature, suggesting that neither gender nor race alone can explain Latina exclusions.

While Latinas have made important strides in closing the representation gap in recent years, they are still far from closing it. For this project, I examined the political journeys of the 32 Latina legislators elected between 1970 and 2024. I conducted archival research, searching through thousands of newspaper articles, campaign websites, and legislative archives. I also conducted personal interviews with 22 of the legislators. In this report, I share some of my findings about the opportunities and challenges that Latinas have and continue to face on the path to the statehouse. Although I make references to specific Latinas at some points, and many of my interviews were on the record, in this report I have chosen to anonymize most of the quotes out of respect for the Latinas that are still in office and who asked for my discretion on certain matters.

Summary of Findings

- Open seats and vacancy appointments have been important electoral opportunities to get Latinas into office.

- Most of the Latinas elected to office are from the Denver metro area. While this is starting to change, there are still many areas with substantial Latine populations that have yet to elect a Latina (or even Latino) representative.

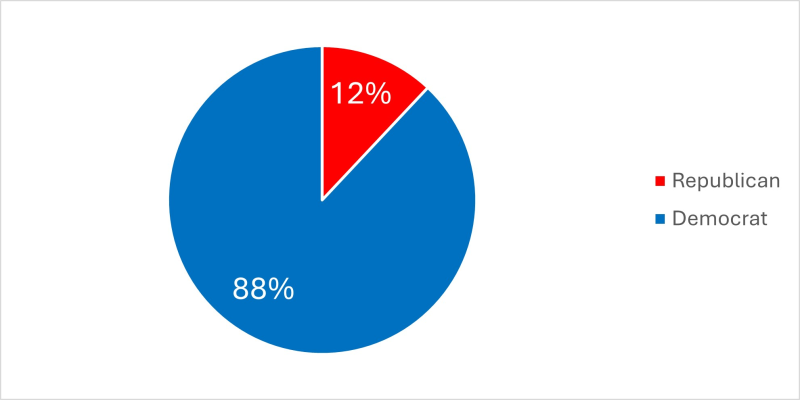

- A vast majority of Latina legislators are affiliated with the Democratic Party, with only four being affiliated with the Republican Party.

- Many Latinas were actively involved in some sort of community activism or advocacy prior to running for office. This advocacy serves as motivation to run, a source of experience, and a means of mobilizing support.

- Party activism, often seen as an extension of community activism by these legislators, has also played an important role in getting Latinas in office. It can play a role in their recruitment and support. However, the relationship between Latinas and (both) political parties is not always a positive one.

- Two of the biggest obstacles faced by Latinas in running for and staying in office are financial resources and discrimination.

Electoral Opportunities

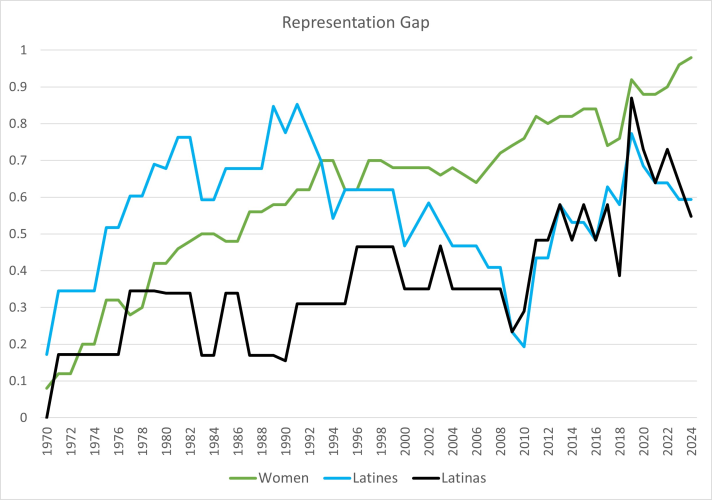

Since their introduction to the statehouse in the 1970s, the number of Latina legislators has remained low, particularly for a rapidly growing population. The Hispanic/Latine community is currently over 22% of the Colorado population, yet there have only been 32 Latinas elected in over 55 years. Figure 1 shows the representation gap for Latinas, as well as how it compares to that of women of all races and Latines of all genders. The values shown represent each group’s percent of legislative seats divided by their percent of Colorado’s population. While the gender gap between Latinos and Latinas closed in the 2010, neither gender has matched the success of white women reaching parity.

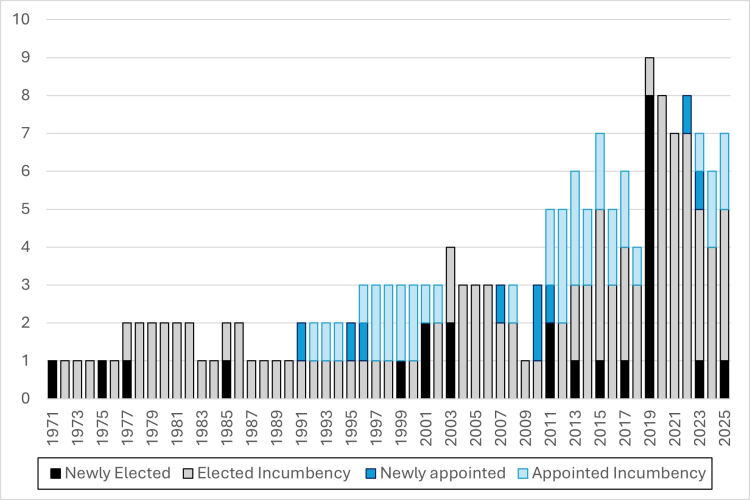

Figure 2 helps illustrate the slow and limited entry of Latinas into the state legislature, making a distinction between the first year a new Latina legislator is elected to office and the subsequent years when they remain. For many elections there are no newly elected Latinas, and the only election where there were more than two is the 2018 election, when a record eight new (and nine total) Latinas were elected. This helps highlight how groundbreaking the 2018 election was for Colorado Latinas. Looking back at Figure 1, we see that this is also the first time since the 1970s that Latinas have closed the racial gap with other Colorado women. A part of my larger project is examining the role that cycles of protest have played for Latina mobilization and representation, both in producing candidates and in mobilizing support for them. The success in this election, however, was not replicated in subsequent years.

Figure 2 also shows the Latinas that have entered office through vacancy appointments and when they have remained in office. In Colorado, if a legislator resigns before the end of their term, they are replaced via a vacancy committee that is made up of members from the same political party as the resigning legislator — usually members of the district’s central committee, precinct leaders, state lawmakers who reside in the district, county commissioners from the districts, and individuals elected as delegates. These committees vary in size. Generally, candidates announce their intent to run and file with the party from which the vacating legislator was affiliated. The committee then votes on the replacement. As can be seen in the figure, appointments through vacancy seats have been an important means of introducing new Latinas into office, as well as in boosting and maintaining representation. Levels would have been much lower otherwise. Nine of the 32 Latinas serving in the General Assembly first came to office via vacancy appointments (see also Appendix A for which Latinas were appointed). Eight of the Latinas appointed via vacancy were Democrats and only one was a Republican.

Open seats have been another important means of electing Latinas (see Figure 3). Of the 23 Latinas that were initially elected to office, only four of them have been challengers to incumbents. The remaining 19 Latinas ran for open seats. This underscores the complex impact of term limits on Latina legislative leadership in Colorado. Most of the Latinas elected to open seats were after 1990, when Colorado adopted term limits and incumbents started "terming out." This opened up new opportunities for Latinas to run. At the same time, six Latinas have termed out of their positions, thus showing how term limits might deplete an already small pool.

The geo-politics of Colorado are another important component of Latina representation and another example of how mobilization plays an important role in electing Latinas. Two of the centers of the Colorado Chicano movement were Denver and Pueblo. They remain the locations with the most advocacy organizations for Latinos (especially Denver). Although Latinos make up large proportions of the population in the most southern parts of the state, very few Latinos – and no Latinas – have been elected to serve in the state legislature there. Twenty-four out of the 32 Latina state legislators have been from the Denver metro counties: Adams, Denver, Arapahoe, and Jefferson (see Figure 4). Pueblo, with its neighboring counties of Otero and Fremont, has had the second highest level of Latina representation, with four Latinas elected. Several other counties have had a single Latina represent them: El Paso (1), Weld (1), Boulder (1), and the mountain counties of Eagle, Garfield, and Pitkin (1).

Party also plays a role in Latina representation in the Colorado Legislature (see Figure 5). Of the 32 Latina legislators, 28 of them served as Democrats and only four of them as Republicans. The first Republican Latina legislator was appointed through a vacancy committee in conservative El Paso County. Stella Garza-Hicks was the legislative assistant to the vacating legislator (he was the first Latino to represent the district). She only served the one remaining year (2008) of that session and declined to run for reelection. The next two Republican Latina legislators were elected in competitive districts that swung red in 2010 (one in Denver metro Jefferson County and the other in Pueblo), a year characterized by the rise of the Tea Party. The fourth Republican Latina legislator was the only one to be elected to the Colorado state Senate, swinging a competitive seat red for one term.

Political Experience and Resources

Many Latinas discussed participation in various social movements as an important part of their political socialization. This was true of the first Latinas elected in the 1970s amidst the Colorado Chicano movement, and for many more Latinas elected later who saw the movement as a formative part of their childhood. More recent generations of Latina legislators were also often involved in various movements (immigration, reproductive rights, anti-war, labor, etc.). Participation or socialization in social movements sometimes led directly to Latinas running for office. Often, however, it led to their participation in ongoing community activism.

Community and party activism are two of the most important means by which Latinas gained the experience, as well as the network and resources, to effectively enter office. Below, I discuss Latina experiences with both, as well as the potential role of formal training in shaping their path to the Colorado legislature.

Community Advocacy

Before running for office, many of the Latina legislators I spoke with were engaged in some type of community advocacy, either as a part of their job or as volunteer work. Many of them had ties to one or more organization. This work was often an important source of motivation. They saw running for office as a means of more effectively doing the work that they were already doing as an advocate. This included the ability to push a particular policy agenda (e.g., healthcare, education, criminal justice, and/or immigration reform) they saw as helping the community, as discussed by these three legislators:

I know what to do medically to help people one-on-one, but every single day I come across something that makes my job more difficult. […] As an advocate, there were limited things that you could do. You could advocate for kids, and talk about your expertise, and talk about what the best policies were, but people don’t necessarily have to listen to you.

Because in the work that I was doing, we were constantly running up against barriers to systems. Barriers to helping people who were dealing with bad landlords, to helping people get their rent paid, to helping kids who were navigating the juvenile justice system and families who were trying to help them as well. And that's what really motivated me. And I went, oh my gosh, I can actually create laws to address these very issues that I see our families facing every single day. And so that was what really drove me to be like, okay, this is, this is the next thing to do.

I mean, you can do this one-on-one, you know, one person at a time, and then a little bit more through advocacy, but public policy… So that was the piece. It was really a lot about understanding public policy and the impact that most of us don't even realize that we can have a piece of that, and how we can change what our everyday lives look like, when we get involved and we have the right legislation in place.

They also discussed representing the community’s interests more broadly, such as this legislator:

I did feel the amount of pressure of…I really have to show up, and I have to win the seat because we have to keep the seat for our Latino community and our representation.

Working in community advocacy was more than just a motivation to run. It also provided invaluable experience for being a legislator.

As a community organizer, and coming from grassroots community, that was what prepared me to be a good and effective legislator, you know, because I know how to stay calm; I know how to bring people together; I am persuasive; and I can build coalitions. That's literally what we do. So, it was hard at the beginning, a steep learning curve. But I definitely felt like I had the tools.

This work was also an important means of developing a network of support. Many of the Latinas ran grassroots campaigns, and their work in the community garnered familiarity and loyalty.

We were out there every night. I had a group of people, and they were dedicated. And we were all out there because I didn't want to go alone. And walking and stuffing envelopes and doing all that stuff. I had a huge group of people who were willing to help me. […] Just, you know, keeping me going and supporting me and believing in me. That, still to me, is just the neatest thing. That's special.

Political Parties

Working with the parties and on campaigns was and continues to be an important pathway for Latinas to enter office. This started with the first three Latinas elected to the statehouse. Betty Benavidez was a party organizer who traveled around to other Mexican-American communities, teaching them “how to raid caucuses.”1 Polly Baca started her political journey as a College Democrat, an intern, and then a student organizer of Viva Kennedy!. Laura DeHerrera volunteered on numerous campaigns and was the secretary for Ruben Valdez, the first Latino speaker of the Colorado House of Representatives, before she decided to run her own campaign.

Legislators discuss their work on other people’s campaigns before their own entry into public office. Sometimes, the party played a direct role in recruiting the Latinas to run.

So probably for over 20 years, I volunteered at my county party and did different things, you know, managing some of those House district campaigns and working on school board campaigns and different things like that…He [local party chair] called me one day and said, “I’d like to meet with you.” I thought he was going to ask me to help coordinate [a campaign]. And that wasn’t what he was going to ask me. He asked me to run. I was kind of shocked because I had never really thought of that.

Parties are also important in that vacancy appointments have been an important point of entry for Latina legislators. Because vacancy committees are comprised of party officials and leaders, having connections to the party can help. Many, but not all, of the Latinas who came to office this way, had close party connections. Stella Garza-Hicks had served as a longtime Republican Party volunteer and then chairperson. As discussed previously, she was also the legislative assistant for the representative leaving office. Mandy Lindsay was also a party volunteer, working on campaigns and Democratic get-out-the-vote efforts. She, too, was the legislative assistant for the representative she replaced.

Sometimes it is in working on these campaigns that Latinas gain the confidence to run for office. One Latina, who had helped on numerous campaigns, recalled being encouraged to run. She initially declined and offered to help recruit a candidate. After explaining how to run a campaign to one relatively inexperienced (male) prospective candidate, she thought to herself, “I can do this.”

Not all Latinas, however, receive party support. A few of them, including Betty Benavidez – the first Latina elected to the Colorado legislature – went against party wishes. They ran against the party incumbent or someone who had a closer relationship with leadership. Some of them even ran against Latinos in the party, which was rarely well received.

No, I didn't actually get any formal support. I think that's one of the biggest, biggest hurdles for Latinas running for office. If you're not a quote-unquote, viable candidate, organizations aren't going to throw their support behind you.

Legislators from the Democratic Party discussed how their support of some more progressive and race-aware issues sometimes put them in tension with Democratic leadership. One Republican legislator discussed her support of women’s and racial issues as impacting party support.

Candidate Training

Candidate training has increasingly been recognized as a way to expand representation for marginalized groups. In Colorado, several of the Latina legislators holding office within the last decade mentioned participating in training programs. Although different programs were referenced, the one most frequently mentioned was Emerge Colorado, whose mission is to “increase the number of Democratic women leaders from diverse backgrounds in public office across Colorado through recruitment, training, and providing a powerful network.” These two legislators discuss how training helped them.

I ended up taking a training course that was really beneficial because it taught you the things you don't know, the moving parts of a campaign. So, it really taught me about that. And really being able to share your story. How you put that out there, how you embrace that, you know, how not to be ashamed of your story, from, you know, your culture, to my domestic violence situation to being homeless. How do you bring all that full circle around? So yes, so that training was really beneficial. And it's really like, it's sisterhood.

I remember having that conversation with that person and her asking me to run. I didn't make the decision right away. I thought, I don't know if this is something I can do. I don't even know what this job involves. I don't know what running for office is like. And so, I started seeking out consultation from folks and just trying to get a good bearing of like, what this all means and what would be involved. And when I decided, somebody sent me an application to apply for Emerge. […] So, I jumped in, finally, after I finished Emerge. I said, “Okay, I'm going to do it. I'm going to do it.” It took me a whole year to make that decision.

While several legislators spoke favorably about candidate training, others spoke of some limitations. A big one was the focus on Denver and lack of attention to other parts of the state, discussed by these two legislators from outside of Denver.

When I think of all the trainings that I did, you know, the candidate trainings, a lot of them are very Denver-centric.

For Democratic policies and outreach, it kills me. I know so many great Latinas, so many great women who would be fantastic in office. But the bottom line is, we don't have an Emerge Pueblo, you know, and I would really like to see a revitalization of Democratic organizing efforts down here in southern Colorado, just because it's not like the voters went away. I think our outreach has just been waning over the last ten years. And until we start seeing and, frankly, supporting these fabulous candidates – candidates like Sarah Martinez, like Sol Sandoval, like Kim Archuletta, you know – things are not going to get better.

Others, such as these two legislators, weren’t as convinced about the relevance or fit of the trainings.

I went through one candidate training a long time ago, but I just was like, I'm an organizer. I spent my entire life as an organizer working on issues and organizing people. …I'm not going to throw away what I've grown up with doing for a textbook narrative of what, how you should run for office.

So, I would say if you're brand-new, it's worth looking into those [things] if you're thinking of running. But don't put complete reliance on them. All of those groups have their own purpose in what they're doing.

One of the legislators discussed the need to diversify the whole political ecosystem. She discussed this in the context of Latinas (and other women of color) participating in a candidate training session.

There were statewide candidates that were looking for finance directors and campaign managers, and they’re like, “I cannot find that person of color to do this job.” We need not only that representation in candidates but also in campaign managers, strategy makers, [and] in lobbyists. A lot of times we don’t see many of people of color. We need to be everywhere, at all levels.”

Obstacles

Although my study focused on only the Latinas who successfully entered office, for a few of them it was after multiple failed attempts. Some lost reelection contests or bids for other offices; some chose not to run again. All of the Latina legislators I interviewed shared important insights on the obstacles they encountered along the way and obstacles that they see other Latinas still struggling with. They discussed money and discrimination most commonly, both as barriers to entry and as ongoing challenges that make it hard (or even impossible) to stay in office.

Financial Barriers

Money has been and continues to be an obstacle to Latinas running for office. In the early years, raising money for campaigns was definitely a hindrance. Several of the early legislators discussed taking on personal debt to run. In recent years, the cost has risen exponentially. While Latinas have become more successful in raising campaign money, financial limitations continue to be a significant hindrance to not only running for but also holding office. Latinas discussed the challenge of having to support themselves and/or their families while also campaigning or legislating. Colorado has a semi-professional legislature, with a session that runs from January through May. Its agenda has grown more packed and is slower moving (requiring significantly longer hours) as polarization has increased. One legislator, who also ran for another office, spoke extensively about the monetary changes:

The biggest challenge was, and honestly continues to be, that I don't come from money.

[For] so many people who run for office, this is what they do in their retirement or they're independently wealthy, and so they can just concentrate on campaigning. So, I would [work] all day and then come home in the evening to either make phone calls to ask for money or I would knock on doors to ask for votes.

I couldn't draw a salary for a good part of the campaign. You can once you are the official nominee, but that takes a little bit. And, and I got resistance about drawing a salary from my campaign to be able to make my mortgage…and you know, eating. I think I was able to get past it because I ended up with a team on my campaign and with outside groups that understood that if you want more and more people to run, these are the decisions that need to be made.

These sentiments were echoed by others, such as these three legislators:

I worked full time while I was running for office because I didn't have a choice.

It hasn't been easy, because I can't quit my job. But you know, when you don't come from wealth like, you gotta hustle. And I think most, not all, most Latinas understand the hustle.

This job is not super well paid. There are other well-paid jobs in leadership, and opportunities. But, if I have kids, it will be impossible for me. I have to commute two and half hours each way on a good day. I live part time in Denver, and I have to rent a place here. So, it would be impossible.

Discrimination

Discrimination continues to be a part of almost every Latina legislator’s political journey. For many Latinas, their early experiences with discrimination played an important part in motivating them to run for office, but it also deters others from running, or for those who do run and get elected, staying in office. Discrimination not only occurs on the campaign trail but also after Latinas take office. It comes in direct and indirect forms from constituents, political opposition, and sometime even from presumed allies. These legislators discussed the various types of discrimination.

When you are the first and trailblazing and people haven't seen someone that looked like you in these positions, there is pushback, which I feel like is the system that is not meant for us, not made for us, trying to protect itself. There were comments of, “how can she represent everyone…she has a Latino agenda.” These are things that my white opponents were not getting.

Sometimes, there are requests that are not made to other legislators. I had an event recently where I was asked if I would interpret. And it was like, “Well, you should just hire someone to interpret. I am here with my legislator hat.”

Sometimes it happens in our own caucus, too. We’ve had things where there is mansplaining or speaking over women.

We had a committee chair, who, despite being a Democrat, was a little hostile about the fact that it was three brown women carrying this bill and did not keep that to herself. And she actively tried to kill it.

We [Latinas] continue to have to work two to three times harder to get half of the recognition that the men do, including Latino men. As much as they say that they are allies and advocates, they aren’t always. So, we really have to continue to push ourselves to advocate for each other, to say, we are here, we need to be part of these conversations, and you need to give us credit for the conversations we have and the work we do. Because that doesn’t always happen.

Several Latinas spoke about legislators (from both parties) being blatant about not wanting to work with them or other women of color or being hostile to the bills that they carried. In a newspaper interview, a Black woman legislator commented that she couldn’t help but notice “that white Democratic lawmakers often seem to have an easier time getting their bills passed, even when those bills concern the same topics.”2 This observation was made by Latinas as well, who discussed being asked to keep their names off legislation or to not speak up at times. Or, when they did want to push forward their own legislation, particularly when it was on issues that disproportionately impacted communities of color, needing a white sponsor to serve as a “validator.”

One legislator was asked not to speak up on a particular issue. She did anyway, and the measure passed.

There's this continuous expectation that if you're a progressive woman of color, you're an angry brown or Black woman. And it's like, like, if there's anyone that knows better how to code switch, it's progressive women of color, and so we know what tone to bring down there. We know what words to use. We know how to address things – honestly, I will say – better than anyone else because we're forced to do it every single day in our lives.

In the 2020s, as polarization has increased, and long-standing norms have diminished, a number of Latinas spoke about being threatened and harassed online, and having to beg for support from leadership.

I’ve seen particular legislators harass, like verbally, or even physically be intimidating towards women.

We were getting phone calls calling me a spic, telling me to go back to Mexico, calling [another legislator] the N word, calling her house N word, like all of these things, like awful, like threatening messages, to the point that people were also on Twitter, when it was Twitter, saying where my son goes to school. It was just so disgusting. And to get our leadership, our speaker at the time, we begged her to do something; to say something…this type of behavior should not be allowed. This is misinformation at its finest. This is like misinformation that is dangerous and puts our lives in danger. And it was like pulling teeth to get her to at least make a statement on the House floor about it, and it still was, not even that great.

I think there's this really gross expectation that we don't, quote unquote, filibuster our own bills. So, a lot of times what happens is you have these people come down with really hateful commentary and messaging at the well during debate, and we're expected to not challenge what they're saying because it'll add time. So why are we supposed to just sit back while they demonize immigrants or talk about women as baby killers or say that anyone who supports the queer community is a groomer? Like, why are we just supposed to be okay with that?

Implications and Takeaways

Although Colorado is a leader in women’s representation, it still has much work to do in closing the representation gaps for those at the intersection of different marginalized identities. This includes Latinas, whose numbers in the general population have far outpaced their numbers in the statehouse. Despite valuable experience in community and party activism, Latinas continue to face significant obstacles in running and holding office. Below are a few takeaways and recommendations to support Latina representation:

- Term limits have had a mixed impact on Latina representation. Open seats are an important electoral opportunity for Latinas to get into office, but it has also served to deplete a limited pool. More proactive efforts to recruit potential candidates are needed to take advantage of the opportunities that term limits provide.

- Most of the Latinas elected to office are from the Denver metro area, while many areas with substantial Latine populations that have yet to elect a Latina. Giving more attention (and resources) to these locales could go a long way in closing the representation gap. One way to do so might be to provide locally conscious and available candidate training.

- Parties could play a huge role in increasing Latina representation. There are already a lot of Latinas active in local parties with valuable experience that could be recruited for open seats or vacancy appointments. Both parties could provide stronger support for Latinas, not only during campaigns but also when they are in office. Even if party leaders can’t stop the discrimination that Latinas face, they can better address it, particularly within their own ranks.

- Community advocacy provides Latinas with motivation, experience, and resources to run. Better recognizing these Latinas as capable and viable candidates (especially by parties and candidate training organizations) could go a long way in growing and diversifying the candidate pool.

- Campaign finance reform or further professionalization of the legislature could potentially help Latinas (and other groups) who have faced financial obstacles. In the meantime, normalizing the use of campaign funds or coming up with other ways to supplement lost or limited incomes might also help.

Future research that expands on these findings might include Latinas who have unsuccessfully run for the Colorado General Assembly, as well as those who have run for and/or held other local offices in Colorado.

Celeste Montoya is Professor of Women & Gender Studies and Political Science at University of Colorado-Boulder. She can be reached at montoyc@colorado.edu.

Suggested Citation: Montoya, Celeste. 2025. "Opportunities and Obstacles for Latina State Legislators in Colorado." Center for American Women and Politics, Eagleton Institute of Politics, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ.

1“Women Dedicated to Better Life.” The Denver Post. August 26, 1969.

2 Alexander Burness. “’Women of color lead and it’s a problem’: How Colorado’s last bill of 2022 died.” The Denver Post. May 17, 2022.

Appendix

Latinas Serving in the Colorado State Legislature

|

Years |

Name |

Chamber |

Party |

Counties |

Entrance |

|

1971-1974 |

Betty Benavidez |

H |

D |

Denver |

Challenger |

|

1975-1986 |

Polly Baca |

H & S |

D |

Adams, Denver |

Open |

|

1977-1982 |

Laura DeHerrera |

H |

D |

Denver |

Open |

|

1985-1998 |

Jeannie Carrillo Reeser |

H |

D |

Adams |

Open |

|

1991-1994 |

Celina Garcia Benavidez |

H |

D |

Denver |

Vacancy |

|

1995-2002 |

Frana Araujo Mace |

H |

D |

Denver |

Vacancy |

|

1996-2000 |

Gloria Leyba |

H |

D |

Denver |

Vacancy |

|

1999-2006 |

Fran Coleman |

H |

D |

Arapahoe, Denver |

Open |

|

2001-2003 |

Desiree Sanchez |

H |

D |

Denver |

Open |

|

2003-2008 |

Dorothy Butcher |

H |

D |

Pueblo |

Open |

|

2003-2010 |

Paula Sandoval |

S |

D |

Denver |

Open |

|

2007-2008 |

Stella Garza Hick |

H |

R |

El Paso |

Vacancy |

|

2010-2013 |

Angela Giron |

S |

D |

Pueblo |

Vacancy |

|

2010-2018 |

Lucia Guzman |

S |

D |

Adams, Denver |

Vacancy |

|

2010-2018 |

Irene Aguilar |

S |

D |

Denver, Jefferson |

Vacancy |

|

2011-2018 |

Crisanta Duran |

H |

D |

Adams, Denver |

Open |

|

2011-2015 |

Libby Szabo |

H |

R |

Jefferson |

Challenger |

|

2013-2017 |

Clarice Navarro-Ratzlaff |

H |

R |

Fremont, Otero, Pueblo |

Open |

|

2015-2018 |

Beth Martinez Humenik |

S |

R |

Adams |

Open |

|

2017-2023 |

Adrienne Benavidez |

H |

D |

Adams |

Open |

|

2019-2020 |

Brianna Buentello |

H |

D |

Fremont, Otero, Pueblo |

Open |

|

2019- |

Monica Duran |

H |

D |

Jefferson |

Open |

|

2019- |

Julie Gonzales |

S |

D |

Denver |

Open |

|

2019-2023 |

Serena Gonzales-Gutierrez |

H |

D |

Denver |

Open |

|

2019-2025 |

Sonya Jaquez-Lewis |

H & S |

D |

Boulder |

Open |

|

2019-2022 |

Kerry Tipper |

H |

D |

Jefferson |

Open |

|

2019-2022 |

Yadira Caraveo |

H |

D |

Adams |

Open |

|

2019-2019 |

Rochelle Galindo |

H |

D |

Weld |

Open |

|

2022- |

Mandy Lindsay |

H |

D |

Arapahoe |

Vacancy |

|

2023- |

Lorena Garcia |

H |

D |

Adams, Jefferson |

Vacancy |

|

2023- |

Elizabeth Velasco |

H |

D |

Eagle, Garfield, Pitkin |

Challenger |

|

2025- |

Cecelia Espenoza |

H |

D |

Denver |

Challenger |