Of Course Women are Among the Most Studious Impeachment Jurors

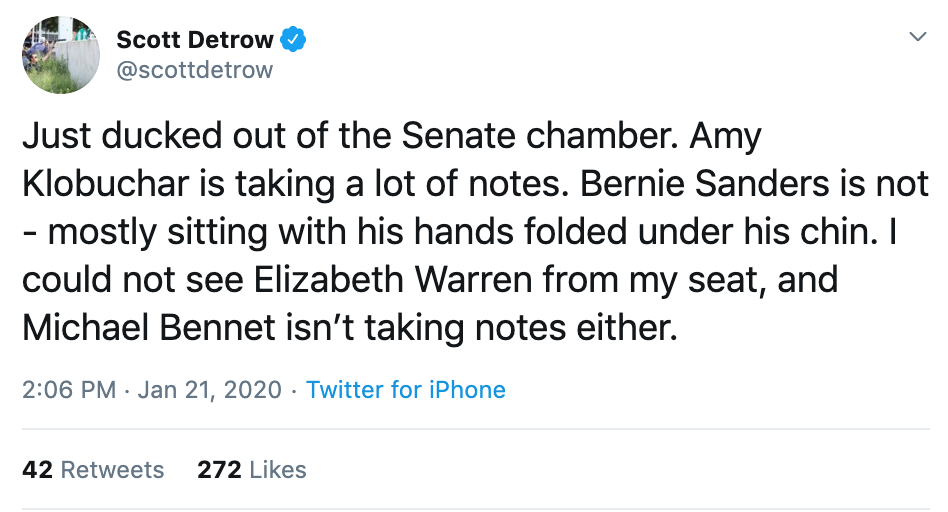

It started on day one of the impeachment trial when NPR’s Scott Detrow tweeted at 2pm on June 21, “Just ducked out of the Senate chamber. Amy Klobuchar is taking a lot of notes. Bernie Sanders is not - mostly sitting with his hands folded under his chin.” Soon after, New York Times sketch artist Art Lein posted an image of Senators Richard Burr and Kelly Loeffler, wherein Burr is laid back in his chair while Loeffler is actively writing on her notepad. Buzzfeed reporter Paul McLeod rated Senator Susan Collins as the “most studious Republican” and Senator Dianne Feinstein as the “most studious Dem” midway through Tuesday’s proceedings.

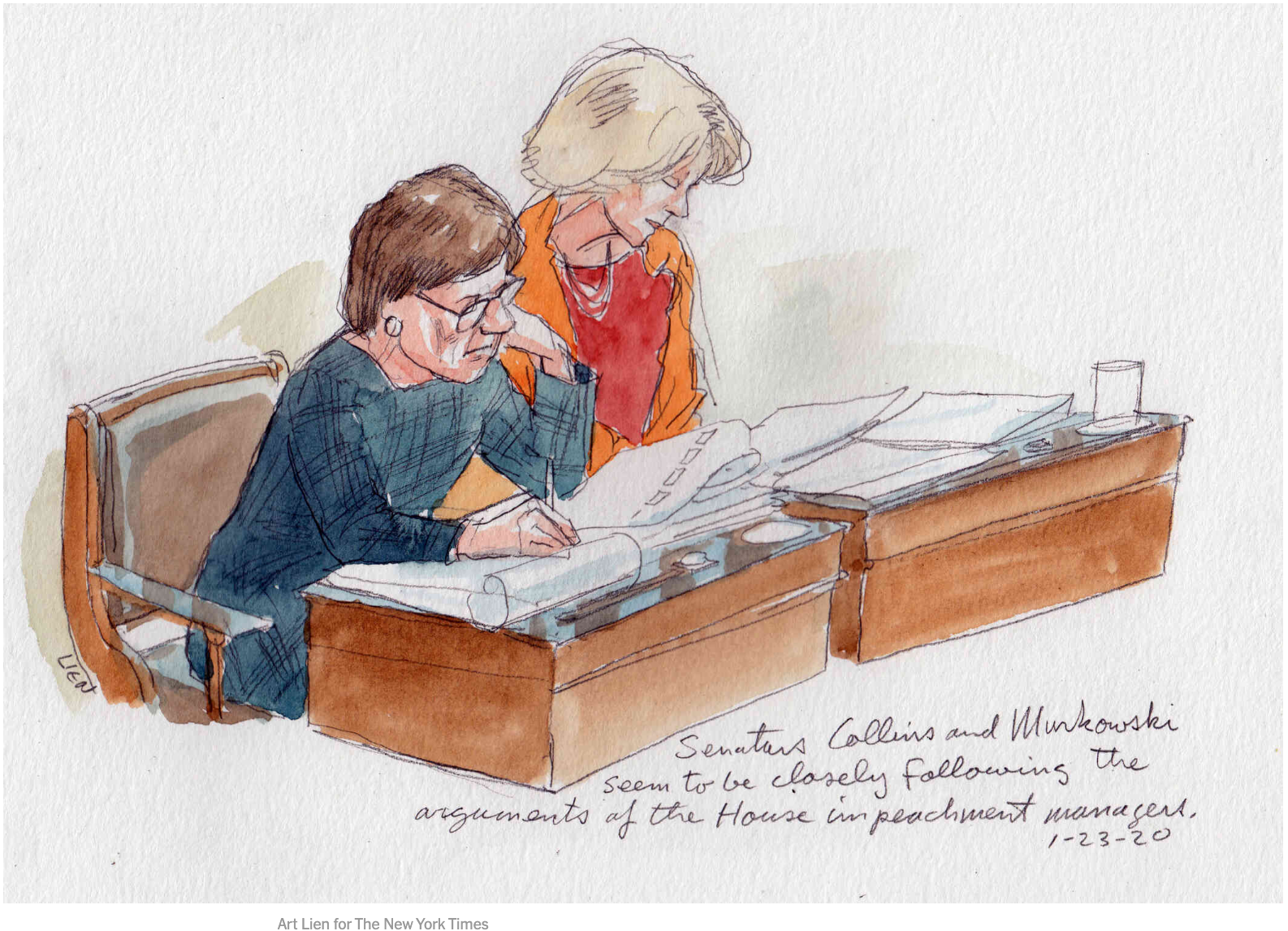

By the second day of opening arguments, Bloomberg reporter Steve Dennis concluded that Senators Susan Collins and Lisa Murkowski were the “Republican senators who appear to be listening most intently, hour after hour,” adding, “I don’t really think it’s a close call.” His observation was bolstered by PBS’ Lisa Desjardins, who called both women “warriors of decorum” (and the Senators most likely in their seats), and sketch artist Art Lein, who drew the pair of women “closely following the arguments of the House impeachment managers,” taking notes and reading documents at their desks.

By day three of the trial, Politico reporters counted three women among the four senators they labeled as “most studious”; in addition to Collins and Murkowski, they described Senator Kirsten Gillibrand’s pen as “almost constantly moving during the many hours of Democrats’ opening arguments.”

These observations suggest a commonality among the Senate’s most engaged pupils: they are women (who, by the way, are still under one-third of all senators). And while we’d need much more information to make any empirical claim that women senators are working harder than their male colleagues this week, that conclusion would not be much of a surprise to those of us who do research on women in politics or, for that matter, to any woman.

Multiple studies on gender differences in Congress reveal that women not only feel pressure to be among the most prepared, but also are among the most productive and effective legislators. When my colleagues and I interviewed more than two-thirds of congresswomen in the 114th Congress, both points were backed by multiple women lawmakers. Representative Rosa DeLauro (D-CT) told us, “Women still have to prove their competency,” adding, “You need to know more than your male colleagues and even some of your female colleagues.” Putting it more clearly, she concluded, “Women have to work harder. That is still very much the case here. And no matter how many times that you demonstrate that you [are competent, you have] to continue to demonstrate it.” Likewise, Representative Kathleen Rice (D-NY) told us, “People are not used to seeing women in these positions. So we have to work twice as hard to prove ourselves.” On women’s effectiveness, Representative Marcia Fudge (D-OH) explained, “I think that women tend to ... be a lot more focused on what the job is, getting the job done, and doing it in a way that is not necessarily adversarial.”

Senator Lisa Murkowski (R-AK) has also talked about women’s achievement-oriented approach to governing; on the day following a January 2016 snowstorm, she presided over a Senate chamber where the few staffers and members that showed up were women. She posited, “Perhaps it speaks to the hardiness of women — that ‘put on your boots and put your hat on and get out and slog through the mess that’s out there’ [spirit].”

Empirical research backs the claim that women get the job done. Studies on legislative effectiveness show that women in the U.S. House sponsor and co-sponsor more bills than their male counterparts, have been more likely than men to get bills passed when serving in the minority party, and have been more successful than their male colleagues in bringing financial resources to their home districts. Why? Lazarus and Steigerwalt suggest that women perceive themselves as more electorally vulnerable than men, leading them to outwork men in Congress across multiple measures. Beyond vulnerability on the campaign trail, however, is the pressure women face to prove themselves within the institution in which they serve. When Representative DeLauro explained that women have to continue to demonstrate their competence in Congress, she was not only talking about demands from constituents and voters; the pressure – not to stumble, not to show any weakness, and never to come unprepared – also comes from navigating a still male-dominant space in which women’s hold and exercise of power remains exceptional instead of normal.

Over the past few months, I have been talking about the additional work women do while campaigning to achieve the same results as men. That fact is backed by evidence that women candidates are not only of better quality than men (on average), but that they face a higher bar in proving to voters that they are both competent and electable. But here’s the thing – they do it and they succeed. The oft-cited claim that “when women run, women win” is accurate, and the 2018 election only affirmed women’s electoral strengths, as we showed in CAWP’s fall 2019 report Unfinished Business. But these two realities co-exist: women work harder to achieve the same success as men.

This week’s commentary on the most attentive senators during the impeachment trial support findings that this burden does not stop once women are elected to office. Whether by writing diligent notes or staying in their seats, women senators both anticipate and adapt to being held to alternative standards than their male colleagues. They remind us that it’s hard work being a woman in Congress, but they are up for it.